Copper, Livingston, Victoria Falls, and a history of British Rule

I got a cheap puddle-jumper out of Maun Botswana after a friend said, “I’m going on a self-drive safari to Chobe and Victoria Falls in Zambia. Do you want to meet me in Kasane? I need to know today.”

From that trip, I learned to leave plenty of time to wait if you’re going to the Botswana Zambia border. So we chose to leave our vehicle in Botswana and hired drivers to take us to and from the border.

I found it interesting that they required everyone to spray their shoes so as not to track unwanted seeds or infections across the border on the Botswana side. Zambia didn’t have the same requirement. I think the hoof and mouth disease that hit the cattle/water buffalo is what prompted such attention. Another difference was Zambia required visas to be paid in dollars. So always bring plenty of dollars to Zambia or you may end up paying a lot more.

After passing through customs, we got in line and boarded the local public ferry on foot.

Standing room was okay since travel across the Zambezi River at this point didn’t take long.

But on the Zambia side of the border, a convoy of 100 soot-belching, copper-carrying semi-trucks waited to be loaded onto the flat-bed boat, one at a time. Then they traveled by land down to Durban, South Africa. The size of the ferry made the wait intolerably long for those crossing from Zambia.

I asked one of the truckers why travel in a convoy knowing there would be a horrendous wait to cross the border.

The driver said, “It’s a shorter wait than getting hijacked at gunpoint. Convoys are the surest way to go.”

This delay also gave the Zambia day laborers a chance to drum up work, something the Zambia-poor government created after giving enormous tax breaks to the privately-owned mining companies.

We maneuvered our way to our connecting ride through a pack of restless laborers.

“You want a ride?”

“Buy my bracelets. They’re made from real copper.”

“You need tomatoes? Onions?”

It made me realize the ecotourism on the Botswana side of the river was doing more than just providing tourists with an exotic backdrop for Christmas cards. Their money was trickling down to all the Tswana.

En route to Livingstone, I saw hectares upon hectares of drought-afflicted branches. What do you do for a country that has such little arable land of commercial value? And those parcels that do produce, are privately owned with next to nothing trickling down to the little guy. I’m not sure if this is a relic of the British social structure, but Zambia could make more of showcasing its wildlife and natural resources to generate more revenue.

At any rate, I hoped to see some of the British-era architecture in Livingstone, a town named after a Scottish missionary–explorer–doctor who was sent down to Anglicize the region. A man with a flawed character, Livingstone did much to further the world’s knowledge of medicine, African geography, and Britain’s Imperial future in Africa. Unfortunately, in the end, he was killed by a lion while struggling with malaria in the bush on his last exploration.

During my short trip to Zambia, what surprised me the most was a depiction at the Livingstone Museum of the African culture pre-1800 and post computer era. It was as if this part of the world never saw the Renaissance, the Industrial Revolution, or any World Wars. Instead, from tribal hunter-gatherers to cell phone carriers, the South African culture evolved rapidly in a short period of time.

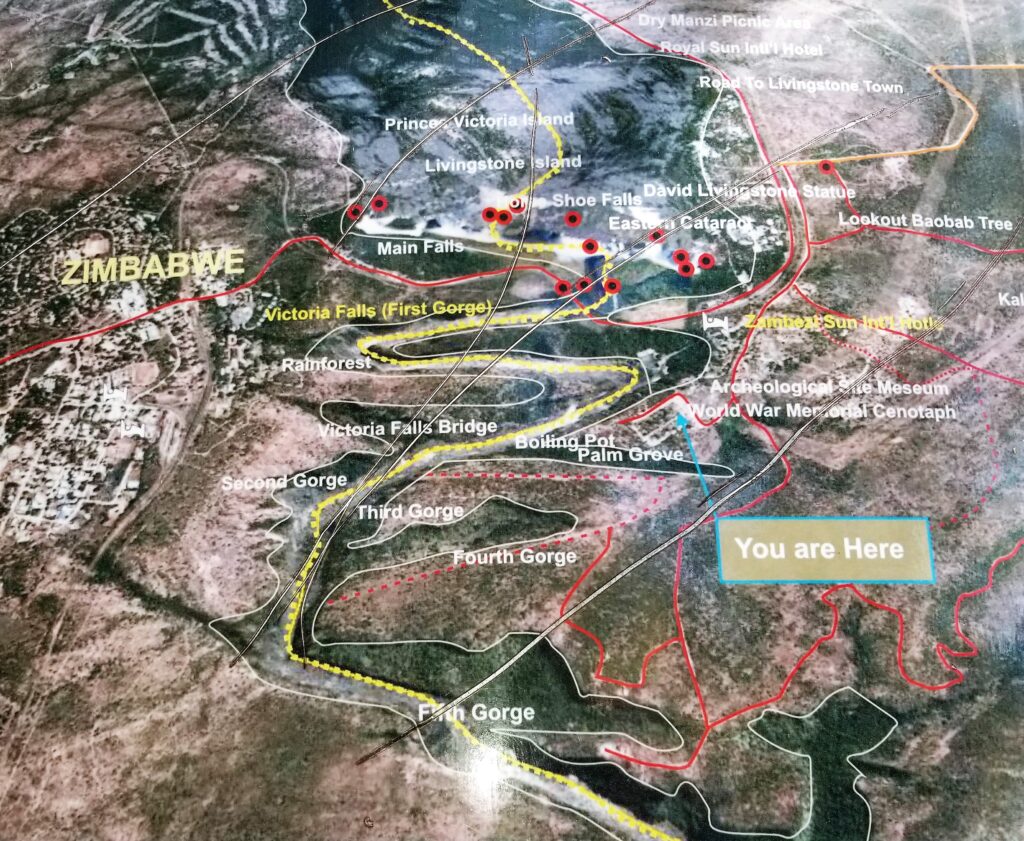

Once we got outside Livingstone we headed to Victoria Falls. There, on the deafening path to the falls, I overhead a tourist say, “Victoria Falls is just another waterfall.” To me, that was like calling the Grand Canyon another hole in the ground.

It’s amazing to see the meandering flow of the Zambezi River right before it drops over The Falls.

I asked the seventy-three-year-old bible teacher traveling on the self-drive safari with me, “How tall are the falls?”

“Three hundred? Four hundred feet tall,” she guessed, shrugging her shoulders. Below us, the Zambezi River boiled as the falls gushed over the rock shelf a mile wide.

“I saw them years ago from the Zimbabwe side when it was still Rhodesia,” she shouted

Zambia was part of the British Colony of Rhodesia until independence in 1964. But unlike Southern Rhodesia, where a 15-year civil war (The Zimbabwe Bush War of Liberation) kept it from being totally free from white rule, Zambia (Northern Rhodesia) became a free nation immediately upon independence from The Empire.

“Why did you leave Rhodesia? I asked.

“The Bush War. We lived on a farm. It wasn’t safe to stay.”

“I heard it was a nasty civil war,” I said. “Fighting in the cities and all.”

“Heavens, no.” She looked surprised. “It was the farms the guerrillas wanted. It was the farms they attacked.”

I asked her if her farm had been under fire. She said, “No. Every night we’d radioed the other farms to make sure everyone was okay. But we always got word from the Reserves before the guerrillas attacked. ”

“Reserves?” I asked. She went on to explain, “Husbands, like my Jim. The government sent them out for six weeks at a time. They put black paint on their faces. Wore old clothes. Couldn’t bathe for weeks because the guerrillas could sniff ‘em out.”

“What did you do when he was gone?”

“I stayed home with the children. She looked into the distance as though reliving the past. “One day after dropping the kids off at school, a group of black teens blocked the whole street. I stopped and waited for them to let me pass. But instead, they walked toward me. I didn’t know what to do. So I drove into the ditch and around them, then gave them an unladylike finger as I sped away.

“Must’ve been scary,” I said.

She nodded. “All us mums with little ones kept personal weapons on us, and the older boys carried rifles everywhere.”

The image of schoolboys in starched white shirts and blue ties toting guns through the academy’s halls came to mind. They had most likely aimed those rifles at people they knew—people who had worked on their farms—people who, like lions on the plain, were roaming the grasslands at night.

“We made it out of Rhodesia to South Africa. But we had to leave everything we owned behind. I can’t say South Africa was much better. Shortly after we arrived, a black teen broke into the house. Stabbed me in the back six times.”

At the Knife Edge Bridge, we stopped speaking, overpowered by The Fall’s thunderous sound.

Then we watched a bungee cord jumper leap from the metal-arched 400-foot Victoria Falls Bridge in the distance.

Tourists! I thought. Risking their lives for what? Such an insult to these people who had been beaten down by so many years of civil war. My thoughts went back to the jobless men at the border crossing, men with no hope for the future. It was no wonder they had post-traumatic stress in their eyes. Then I remembered Wisdom, a Zimbabwean I’d met in Botswana.

I’d met Wisdom on one of my daily walks along a tributary to the Thamalkane River.

“What are you making?” I’d asked the slender, Black man in blue overalls digging a two-foot-wide ditch.

He greeted me with a bright, comforting smile. “This will be a fence,” he said and pointed at the one on the next property. “Like that—with lights.”

“Do you always work alone?” I asked.

“No. The others had to go. I live just over there.” He nodded at a concrete building no bigger than an eight-foot-square shed. “I told them I would finish up for the day.”

“You have a different accent,” I said. “Where are you from?”

“Zimbabwe,” he answered.

I was puzzled. “I thought things got better for Blacks after The Bush War.”

“I could not find work there.” He looked down as if gathering his thoughts. “I cannot say The War was wrong. Before the fighting, it cost us almost half our monthly salary for transport. The Whites would not listen when we complained. But after The War…Well, we should not have wanted it all. We should have worked with the white people. Learned how to farm their land, use the equipment in their factories. Then shared the country. Now it sits broken, so I must travel here to feed my family.

“I’ve heard the local Tswana say Zimbabwean laborers work too hard—show them up.”

He shook off the compliment. “I do what I must and go wherever there is work.” Then he lifted his shovel and continued to dig. As I waved goodbye, I thought Wisdom seemed to be precisely that, wise. It was as if his soul had chosen his name.