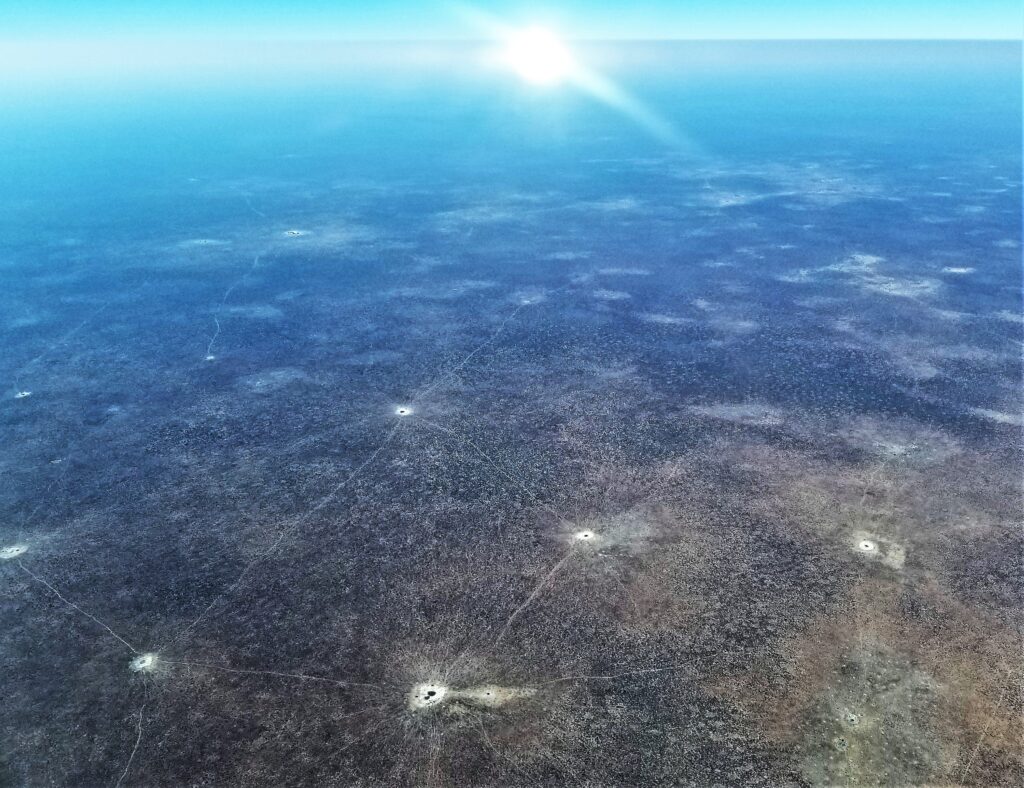

From the circular window of a turboprop jet, the view of an endless African plain stretched in all directions—no roads, no people, only beaten down paths from water hole to water hole. Exhausted after traveling for thirty hours, I wondered if I’d be landing in a dusty donkey town or a dream oasis.

I’d heard Maun was once an ugly, remote trading post for big-game hunters and Sans Bushmen. But it outlived the malaria-riddled days with soot-filled lanterns hanging next to canvas-wrapped cots to become a photo-safari jumping-off point in Botswana. Yet it wasn’t the glamour of a safari that drew me there. So why had I traveled halfway around the world?

After getting a restless night’s sleep, I pushed myself out of bed and into the hot, dry air to explore. The first thing I did was stock up at the ‘Old Mall’ where the locals shopped. Women from the Herero tribe, in long flowing, sequin-studded dresses and matching square, flat hats, lugged sacks of groceries curbside where they waited for the next taxi. Many of the Herero tribe had migrated to Botswana years ago when a brutal history saw about 80% of their people exterminated in Namibia by the colonial government.

My bad-ass friend Marenga is the one squatting on the lower left at her sister’s wedding.

Marenga, a bookkeeper, and I met outside the closed library where she, Patience, and Innocent were using the WIFI for free. What an inconvenient time to get a ‘could-not-miss’ phone call.

After about 30 minutes waiting curbside at Old Mall, I got a taxi. That’s when I met Gadaphi. Opening the door, I jumped in the back and told him, “Coca-Cola Road.” Then I pointed in the direction of my place. One could only guess how the cabbies found their way around the web of unpaved roads, dotted with metal-roof or thatched mud huts that sold soda, canned milk, and mobile phone recharge minutes.

“You’re from Maun?” I yelled over the noise of a pickup truck backfiring.

“No. Francistown. Studied marketing. But there was no work there,” Gadaphi answered, with an easy-going resignation in his voice.

Not far from the center of town, we turned left off the asphalt pavement onto a white-sand path where every inch had been scoured for firewood, leaving only the bare ground for chickens to scratch.

“Here’s my cell number,” Gadaphi said when we arrived at my bougainvillea shrouded gate and handed me a ripped piece of paper with scribbles. “Call me if you need a ride.”

From then on, Gadaphi became my go-to driver around town—including the Mission church where they danced down the aisle and told sermons about wayward American women who were misled, got pregnant, then found their way.

Shortly after getting out of Gadaphi’s taxi, I placed my purchases in the metal cupboards and humming fridge, then I struck out on the trail along the river that fronted my home-away-from-home.

Like walking along an ocean beach, my feet sank half a foot for every step in the dry sand.

The sun was just setting, so it was too early for the hippos to surface and purge their lungs with loud flatulent-sounding calls. Still, I walked quickly. Hippos may look like clumsy lumps of blubber, but they’re unpredictable and strike like lightning, making them the deadliest animal in Africa.

On my return to my three-room house on the Thamalakane River, a flock of children raced up, out of nowhere and surrounded me. One of the braver girls, about nine years old, with long spindly legs and a shaved head, pushed in front of the others. Then with a coy innocence that fooled no one, said, “Give me pula.”

“Sorry, I have no money,” I told her truthfully. It was inside the lushly landscaped AirBnB.

Eyes flaring, she yelled in disbelief. “Aren’t you American?” She waited for me to find some coins in my pocket but I had none. Disappointed she said, “My name is Bontle—it means beautiful.” And she was with cedar-brown, silky-smooth skin. But beneath her lovely exterior, I saw a tough little spirit.

A woman’s voice called out from a distance. Wide-eyed with alarm, the children picked up their firewood and scurried off down a different path.

“Goodbye, my friend,” the bald Bontle yelled back. Thus began the first of our daily greetings.

Several weeks later, on my weekly grocery shopping excursion into town, I stopped by a small, sparsely furnished office with an overhead fan, to get a quote on four-wheel-drive car hire (rental). The agent and I talked about the 4×4 truck, what the road was like to the reserve where I’d be driving it in about a month, and other things. I learned he grew up in Maun, went to senior secondary school, and was the oldest son in his family. I told him I owned a four-wheel drive back home and had driven it in the mountains.

“When we return from the reserve, I’ll give you my 20-liter gas can,” I told him.

The one I needed to buy because there was only one gas station every four hours. That way, he could ‘loan’ it to other tourists for a fee and maybe not notice any scratches on the truck when I brought it back.

He smiled knowingly.

After we shook hands, I stepped out into the hot sun and meandered over to a cluster of trees where taxi drivers hung out. With no bus service in town and few private vehicles, cabbies always had work. Whether it was enough to pay the bills was a different issue.

Next to the dirt parking spot, safari jeeps with high-riding, nine-seater, canvas-topped 4x4s and tourists with wide-brimmed hats sporting tailored clothing waited for their groceries to be loaded. They were going on a guide-driven safari, where everything was taken care of for them, from tents to candle-lit drinking binges. And hopefully, a life-long experience worth every cent of it.

A week later, my friends and I flew into the Okavango Delta on a six-seater plane. Under us, a swampy archipelago of tear-drop-shaped islands grew then shrunk, as a ribbon of Angola’s flood-waters drowned the connecting land bridges. The network of branching paths from landmass to landmass, beaten down by wild game, reminded me of an old saying, ‘All who wander are not lost.’ Again, I wondered, “Why was I here?”

Just before we touched down, a man nonchalantly chased baboons and warthogs off the landing strip. From there, a boat carried us through undisturbed World Heritage marshland to our lodge.

Within the pristine swamp’s borders, there were no barriers. So Elephants tromped between tents while crocodiles sunned themselves at the base of boat launches.

Sexual boundaries were also ignored, and infection by HIV was rampant.

“How many weeks at a time do you work in the Delta?” I asked an apron-clad woman as she prepared a ‘stuff-yourself’ white-tablecloth buffet.

“My shift is six weeks on the job, two at home.” She gave me a hesitant smile. “Wish I didn’t have to be away from my little girl so long. But many from Maun work out here. We need the money that Delta jobs pay.”

It struck me such an arrangement was a recipe for trouble when a wife or husband stayed away from home for too long. And I noticed one of the bush guides give her a long, satisfied look. She scowled at him. Like many Botswana females, she had fully endowed buttocks, something her co-worker seemed to find pleasing.

Later that night, with the soothing sound of the delta waters lapping against the lodge’s wood pilings, the conversation grew loud and lively. Khaki-uniformed men carrying perspiring bottles of wine wrapped in white cloth filled our glasses to the brim.

“Did you know Botswana has the highest incidence of HIV and syphilis infection in all of Africa?” a tourist asked.

“That’s statistics,” our guide answered, unfazed. “Botswana just does a better job of collecting data than our neighbors.”

“Aren’t you afraid of getting AIDS?”

“A man will be a man,” he chuckled. “Everyone dies eventually.”

But do all your partners think that way, I wondered. And for the rest of our stay, I watched their sexual dance play out and marveled at the wildlife.

A month later, the Monday arrived for me to pick up the 4×4 and start our self-drive safari. I was nervous, never having driven through drifts of sand before with animals crossing at will.

We’d rented a tent on stilts in Khwai, a land development reserve run by local villagers.

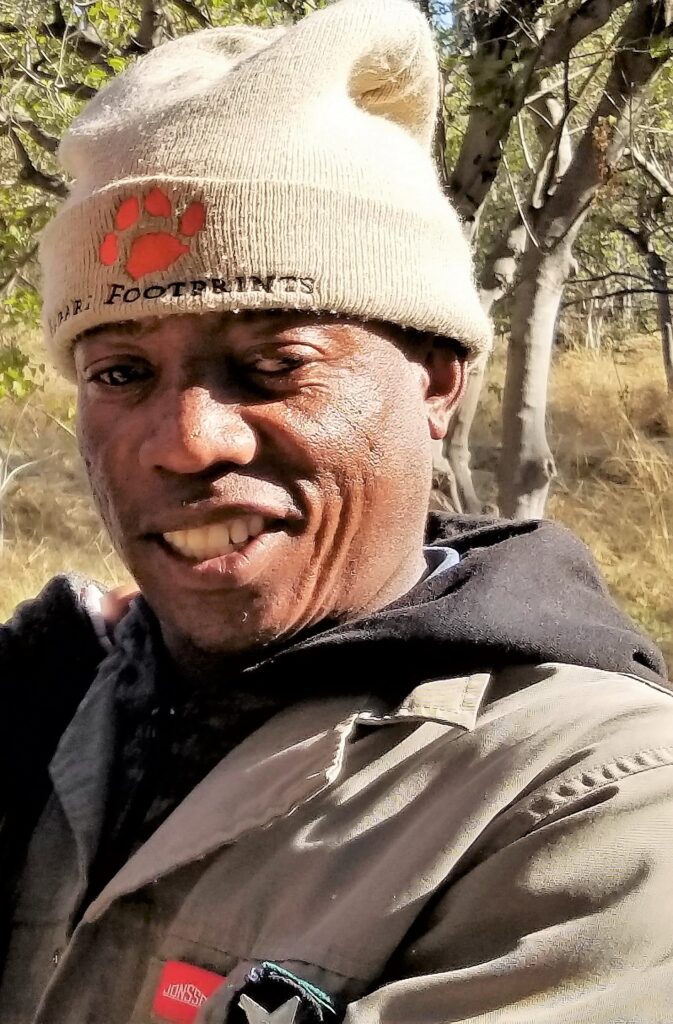

The only thing missing was a guide. But it was peak season, and everyone was booked. So I hired the caretaker of our rental, T-man, a local Sans Bushman.

Immediately after we arrived, we drove down an animal trail along a stream, twigs slapping the truck, blinding me at every curve.

Twilight cloaked the horizon with a ruby red glow. I was exhausted after the six-hour drive from Maun but drove on.

“Closer,” T-man urged. “Go farther down the path.” His voice was monotone, but his body was tense.

Along the stream, elephants ripped clumps of long, waxy leaves out of the water, then ground them into a pulp. It would be their last meal of the day because the predators had them on the run at night.

Suddenly, deep, from within the nearby bushes, a cacophony of bickering birds broke out in alarm. The tall upland grasses on our left rustled. At the sight of a leopard, we stopped. It was time for her to eat.

“I’m going back to camp,” I said and made a three-point turn in the sandy path. Call me a wimp, I thought. But there was no way I’d get stuck in that saturated quicksand to become her next meal. The light-brown bushman pulled his knit cap low, then crossed his arms. He’d never driven a car before and didn’t understand we could get stalled. And I wasn’t getting out of that truck to dig us out.

After a relaxing stay in Khwai, we returned to Maun. Weeks passed. I found a licensed guide and this time, when I took my daughter to Khwai, he drove to the reserve. I realized there were some things I shouldn’t have cut from my budget—like a driver who understood the bush. A friend suggested I call the Land Trust, who told me to contact someone they knew, who had me call someone else, who knew of someone I really should hire. The guide was a stranger to all of them, and I’d be spending twenty-four hours a day for seven days with him nonstop. Eventually, we met. He wore a leather safari hat, was tall, limped on his left leg, said his name was Rogers, and I was supposed to trust him. So I did.

Rogers had the bush under his nails, doused through his hair, and cemented in his soul. He told me stories of when as a child he had trailed through the village behind his uncle, a man of respect, who had rallied the tribes to support Sir Seretse Khama when he ran for president instead of remaining a bush king. Certainly a gentleman by any definition, Rogers told me while I was unloading a cooler from the truck, “I have a wife and know that women are strong but sometimes their pride won’t let them ask for help.”

One night after we returned from our game ride, I stood by the open-pit fire at the edge of our tent-on-stilts, cooking chicken while the others relaxed on the balcony. I heard rutting calls from some antelope in the trees nearby. Shortly after, they were replaced by a hollow whistle. Then there was nothing—until Rogers came rushing down the stairs.

“What are you doing?” he asked frantically, dusting the area with the beam of his flashlight and clutching a knife in his other hand. “Hyenas have come.”

Rogers explained how several hyenas had smelled the sizzling chicken fat and were prowling only feet away. So upon catching sight of them, the antelope warned each other with their whistles to flee. Communications among animals in the bush seemed so intuitive. Why was it hard for humans to understand each other? My thoughts went to T-man.

One day, when Rogers returned from visiting T-man in his hut, he told me, “T-man and his wife sit in the same room for hours and don’t talk. They don’t use words; instead, Bushmen use their bodies to speak for them.” I couldn’t imagine passing a night with no computer, no phone, no books, and no conversation. It was as if the bushman had a sixth sense that I couldn’t perceive. I thought of the game rides we’d gone on with him. He could have been shouting at me with his body talk, but I heard none of it. I’d become too dependent on words, text, and emails to see there were other ways of connecting.

A couple of days later, T-man’s wife shuffled over to our shared water spigot and filled a plastic jug. She looked at me but said nothing. Still, I felt her unspoken nudge.

“I saw you getting off the bus yesterday. Were you returning from work?” I asked.

“No, from Mababe,” she answered.

“You go there often?” I remembered the village as the only petrol stop for hours.

“My son is sick. He has been crying every night for days. We saw the doctor, but he had no medicine. So he told us to come back another time. But we don’t know when they’ll get the pills our baby needs.”

I’d seen the baby’s runny nose and rheumy eyes but thought it was nothing more than a cold. The thought of the antibiotic pills back home that were thrown away once the expiration date passed, even if they were still good, made me angry. Pills that wouldn’t be shipped to Africa because someone could be sued. Pills that could save a baby’s life that were flushed down the toilet. Before we returned to Maun, hoping to make amends for not hearing the caretaker’s body language on my first trip, I set some money aside in an envelope for their baby. For T-man’s pride and joy. For his wife’s love of her life. For naught, if there were no pills to be bought.

Finally, the time came for me to leave Botswana. I took my last walk along the river.

“Hello, my friend.”

I turned to see Bontle and her pack of friends rush up from the water’s edge.

“What have you brought me today?” she asked.

I’d taken to handing out bouncy balls and lollipops, but I had nothing that day. So I said, “Let me show you something instead.”

I unslung my binoculars, then gave them to her. “Look through here,” I said and pointed at the two rubber-rimmed eye-pieces.

With a look of smug satisfaction, she put them up to her face. But her expression quickly changed to doubt. Then as if the binocs were cursed, she held them out for me to take them away.

“My turn,” her brother said. One by one, the binoculars traveled from child to child. Each of them getting more excited, their high-pitched voices babbling nonstop. Finally, it reached Goitse. A quiet girl, taller than the rest.

Hesitantly, she raised the binoculars—backward—with the larger lens to her eyes and saw nothing.

I turned them around. “Try again.”

Goitse grasped the binoculars limply at first, slowly scanning the ground in front of her, where a brown and white cow grazed on the edge of the floodplain. Quickly, she stepped back as the viewfinder leveled on the gentle giant’s dark eyes. Under the lenses, they must’ve been as large as two moons. From there, Goitse tracked an African hornbill flying between the trees, cackling and wobbling on branches in a drunken stupor.

As she swung the binocs skyward, my eyes followed her path up to billowing clouds that morphed into mythological gods. Then dreamlike, the sun soaked the white pillows in the sky.

When Goitse pulled the lens away, I was struck by the naked emotion on her face and wonder in her eyes.

Finally, I realized why I went to Botswana. I had, as they say in Swahili, gone on a safari, but not to see wildlife. Instead, I journeyed inward to rediscover the magic in life that I had buried under layers of knowledge. Thanks to Goitse, I saw dream-like illusions in the sky by looking at the world through the eyes of a curious child.