More coming.

Statement about life in Havana on a construction partition along Paseo del Prado.

At the Havana airport, taxi tickets are sold curbside. Since Cuba doesn’t manufacture cars, most taxis are 1950 US models or Russian-made. I wish we would’ve gotten one of the old US models. Instead, we got a 30-seater school bus to transport three people. My friend was sure we were being kidnapped. But every driver, regardless of the number of seats in their vehicle, takes their turn. That’s socialism for you.

Our flight into Havana was late, very late. We arrived at the art-deco Hotel Sevilla, a 1950’s gangster hangout, at almost midnight, starving. We were sent to the restaurant on the top floor, exhausted. The fish was cold. The tortillas were stale. They were out of white wine. But who cared? They were performing an opera. I love opera. So that’s how my trip to Cuba began: with refined culture.

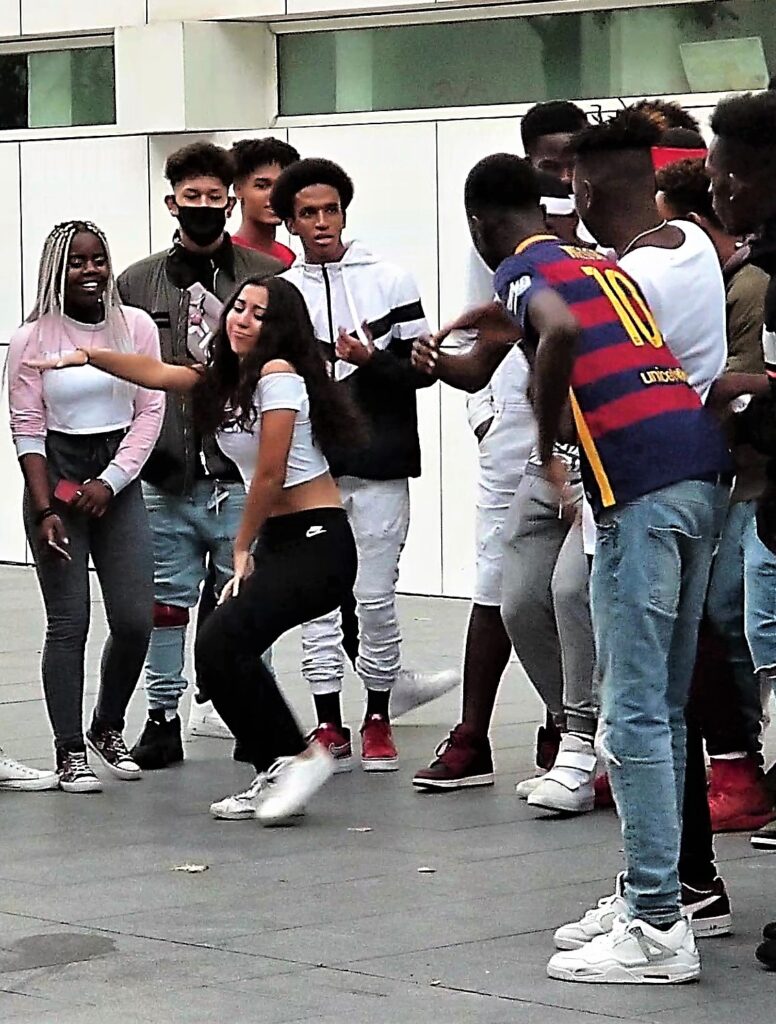

There was free music everywhere, from a symphony in the plaza fronting La Catedral de la Virgin Maria de la Concepcion Immaculada de la Havana,

To cumbia on the veranda of the Grand Theatro Havana

And salsa (I love salsa too) in Trinidad, where one man danced with two women at the same time. I was totally impressed and a little jealous of the ladies.

But I suggest you get a review of all hostals where you plan to stay. Two hostals in Trinidad scared the daylights out of my friend. First, we were conned into checking out a strange boarding facility. You know, when they tell you the wrong directions and bring you to a location where you had no intention of going. The second was at the hostal where I’d made the reservation. Sure, it was unusual to see photos of a naked young man on the walls. But when they turned out to be the proprietor’s son, that was creepy. Made me question what oversight the state provided.

Isn’t that socialism for you: free directions, free music, free education, and free health. So why is the city of Havana falling apart?

On this trip, I met up with two old friends, a former fellow high school teacher, and her husband. As educators of migrant kids escaping poverty in Latin America, we compared the pros and cons of our students having chosen democracy in the US to socialism in Cuba. Which was better?

Unemployment in Cuba may be low, but so are salaries, with workers taking any jobs they can get, even though there is a lot of work yet to be done upgrading Havana’s infrastructure. It’s crumbling. In part from the salty air. But also, I suspect the concrete was made with salty sand from the nearby bay, Bahia de Habana. What a shame with such stunning architecture.

Unfortunately, I fear developers from foreign countries will offer the Cuban government a deal: fix the deteriorating infrastructure at a price they can’t refuse. But I don’t want to see Cuba taken advantage of. I’m not saying that all developers are sharks or all Cubans are naïve: still, it’s much easier for both sides to visualize a better future than to implement it in a way that everyone feels they’ve gotten what they bargained for.

After the 1959 revolution, the socialist mentality inhibited those who were proactive about doing new things and achieving their dreams. As a result, one of Cuba’s greatest exports has been its entrepreneurs: talented immigrants to other countries, something that has made the US so great. So, who was left to take the lead and improve the country’s economy? How was funding to be generated to refurbish everything that should be fixed?

Deteriorating buildings seen from Havana’s skyline along Paseo del Prado, such as the Gran Teatro Habana, are reminders of what Cuba has to offer. The Port of Havana and Castillo de Los Tres Reyes del Morro along the entrance canal in the background on the right could generate more tourism revenue if they were made sparkling strong.

Quickly we learned to seek out private cafes with restauranteurs who had daring hearts. Unfortunately, diners supported by the state served food that tasted like it had been reheated several times, and the menus were as dull as yesterday’s news. So why go to Cuba if it’s seen better days?

Of course, the lure of seeing the Cuba of Hemmingway has kept tourists coming.

Los Ambos Hotel: one of Hemmingway’s favorite places to stay, looked pretty swanky for someone on a writer’s salary.

And La Bodeguita del Medio Mojito, his favorite watering hole, is just around the corner.

For the more sophisticated with deeper pockets, there’s the Hotel Santa Isabel.

Or the San Felipe y Santiago de Bejucal Hotel, a paradise many nostalgic Cuban exiles remember.

But the ecosystem is devastated by overuse. The reefs are dying. Wetlands are silting up. Cuba just doesn’t have the resources to save its assets.

The waters may be turquoise blue, but where are the fish?

We woke at 6 am In Guama, the most important wetland in the Caribbean, to a boat waiting outside our cabana. The man in the boat, our bird-watching guide, had been educated to become a physician. But he couldn’t find work in his chosen field. Without a thriving economy, everything suffers.

But some are cautiously pushing the envelope of entrepreneurship for a better life. Some businessmen are balancing old-style hospitality with a capitalism-variant for a better future.

Hostal de Luis in Playa Giron is located at the entrance to the Bay of Pigs.

Luis had been a chef at a five-star hotel before he started his own hostal. He learned to barter for the tiles he needed to enhance his property and negotiate for a license to service several hostals under one roof. Getting a new windshield for his 1950s car meant offering meals to tourists staying in other hostals to supplement his income. But he had something unique to offer: the best sea food and intricate side dishes I ate in all of Cuba.

If you want to get around the Bay of Pigs, don’t expect to see many cars. Instead of bicycles or motor tuk-tuks, you have horse-pulled wagons to give you a lift.

And all food is still delivered the old-fashion way, horse and buggy.

In Havana, the old 1950-era cars seem plentiful, but that’s the only place they’re seen in any numbers. Roads between other towns and villages have few vehicles other than sooty trucks. If only the economy would pick up.

But socialism today, tomorrow, and forever has been good for many Cubans. Where else in Latin America has the extreme class division that exists with military dictatorships been leveled with one political overthrow?

Where else in Latin America has the quality of life improved for everyone, not just the upper class?

Where else do people feel safe on the street at any hour, regardless of the neighborhood?

Cuba was once a diamond in the rough. But the rough has been wearing down. And all that was once grand about this country will be gone if things don’t change. After the 1959 revolution against the military dictatorship, the US imposed an ongoing embargo while the Soviet Union subsidized Cuba with three times the allocation the US spent on all Latin American countries it supported. But the Cuban economy was inefficient and overspecialized, not sustainable without foreign aid. When the Cold War ended, subsidies from Russia stopped. Then the sugar market crashed, resulting in a stagnant economy. And the Cuban business model, based on the old Soviet Union’s centralized planning theory, was no longer ideal. In recent years, the state has started to play a less active role in the economy and support a cooperative variant of socialism. And as of 2019, voters approved a constitution granting the right to private property as well as access to free markets. Foreign investment and private Cuban-run businesses have increased. Hopefully, a socialist-variant government will evolve without being a totalitarian dictatorship. And free music, free education, and free health services will continue to be available to all.

Fidel Castro was a political leader from 1959 to 2008. He was a true friend to Russia and believed in the power of Marxist-Leninist socialism, where businesses and industries are nationalized and the state controls social reforms. Castro’s supporters view him as a champion of socialism and anti-imperialism. His revolutionary government advanced economic and social justice while securing Cuba’s independence from other countries trying to impose their ideals. On the other hand, critics called him a dictator, with an administration that oversaw forced disappearances, degrading treatment of political dissidents, and a downturn in the economy.

The Malecon in Cuba could be like the waterfront Embarcaderos in other countries, thriving with a financial district, tourism, and a wide variety of commercial enterprises. Instead, most of the buildings lay vacant.

It was speculated Raul Castro, Fidel’s younger brother, would usher in economic reforms. But during his presidency, starting in 2009, the economy plummeted. Was the downturn a coincidence with a worldwide recession hitting all countries? Or the fact that Cubans had not been given full freedom, fair elections, or civil liberties enjoyed in other countries, so the motivation wasn’t there? At any rate, Cuba is stuck in the past. Somehow it needs to pull itself into the 21 century.

Who were the Cuban Five, otherwise known as the Miami Five? In 1998 they were arrested and later convicted of conspiracy to espionage, murder, and other illegal activities. After denying it for three years, in 2001, the Cuban government acknowledged that the five were intelligence agents. The US government was told they were spying on Miami’s Cuban exile community, not the government. Cuba said the men were sent to South Florida in the wake of several terrorist bombings in Havana organized by anti-communist who had hopes of re-establishing a flourishing capitalist government. But maybe the government just wanted to reclaim funds smuggled out of Cuba by the exiles. That would have been short-term thinking, not a long-term solution.

When harvest time rolled around at the high school where my friend and I taught, fifty percent of our students were absent, they were out in the fields. Instead of going to class, they were picking tomatoes, apricots, walnuts, or other cash crops in California’s Central Valley. Doing work that minimum wage earners refused to do and paying taxes on their earnings. Some of our students who immigrated to the US learned English. Others did not. Some assimilated themselves into the US culture. Others did not. Some had Green Cards. Some kept those Green Cards up to date. Others did not. Without a Green Card, they lived in fear of being deported or unable to return to the US if they went home to see their families. And many had children born in the US that they would have to leave behind. My friends and I wondered whether our students would have had the same quality of life had they lived in a country like Cuba. Economically they didn’t fare better, although they were able to send money home, but they had to live in houses with multiple families and little personal space. Income is less in Cuba, but they would have free education, health services, and basic food provisions. In Cuba, civil and economic liberties would be constrained. But in the US, they didn’t vote, they didn’t own private property, and few tried to establish their own businesses. In the long run, the only difference I see is being with family.

Cuba’s socialism was a hard road to travel. It’s not the answer for all struggling countries. Unfortunately, life has gotten more complex since 1959, we’ve become a one-world community. Something should be done to make sure places at risk don’t succumb to criminal wars, instead, hopefully, they’ll discover a route to peace and stability. So what’s the best way other countries can help those in need? Ask the people, not just the government.

I was told J.R.R Tolkien vacationed in the Drakensberg escarpment as a child. With such a fertile mind, I’m sure images, such as the rock formation in the background (below), known as the castle, helped Tolkien spin stories at an early age.

My plane from Johannesburg to Pietermaritzburg was delayed by three hours. That wouldn’t have been bad had I not arrived at eleven in the evening, with another 90 minutes of driving in a rental car on the opposite side of the road.

On top of that, I had to pass through several townships in the dark of night to a place I’d never been to before. The first township I drove through was ablaze with fires. Wildfires? I asked myself. No, they were burning trash.

KwaZulu-Natal Province, homeland of the Zulu tribe, has the second-largest economy in South Africa. But I was there to hike the Drakensberg Mountains and see Bushman rock art.

Jurassic lava flows cap much of the rock formations. The result is a range of exotic flora.

These Clarens formations, or lava overlayed on a desert, are found only in Lesotho and KwaZulu-Natal.

And there are lots of Bushman fossils hidden in hills.

Yet as gentle as the land may appear, hiking is not for the faint of heart. It goes straight up.

But there are rewards every step of the way.

Pillow cave looking at Rhino Peak.

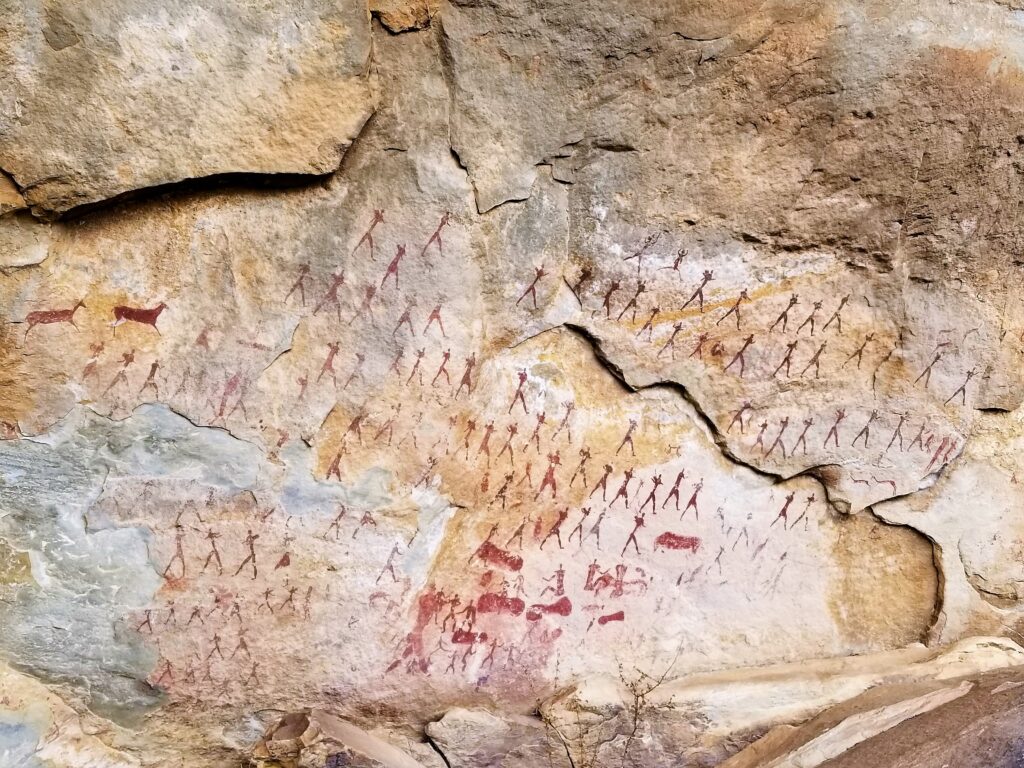

The formation with the bushman rock art is in the middle of the ‘flat’ green expanse.

This view is from the backside of the rock art.

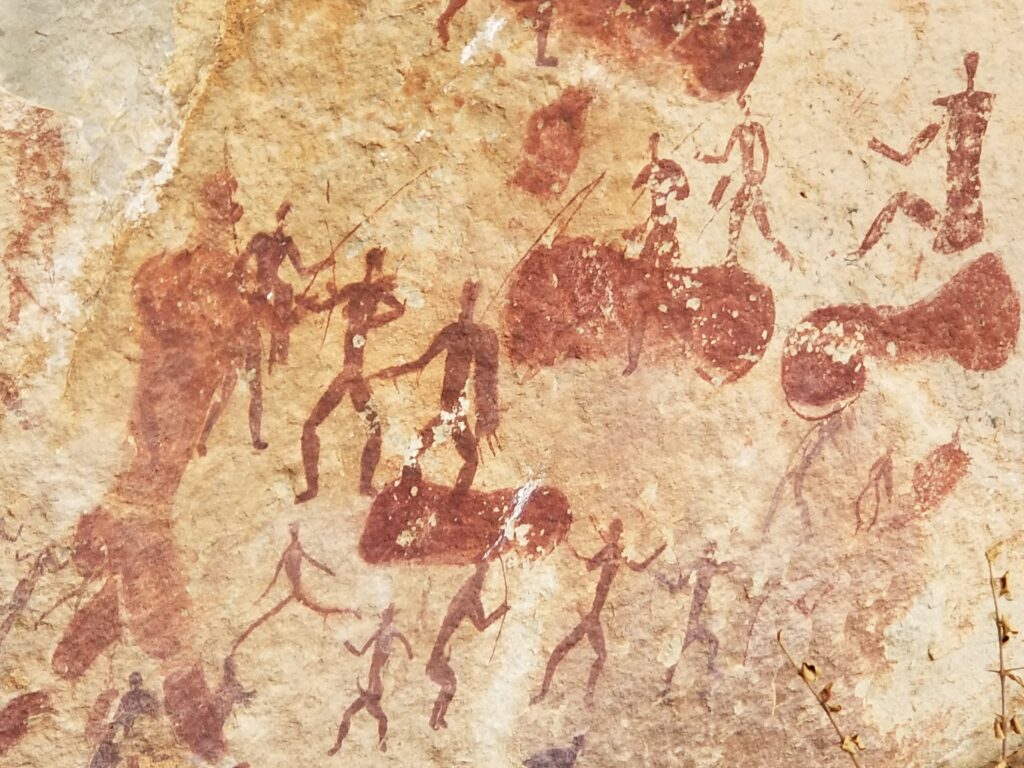

From the front or protected side, the bushmen painted their stories.

Their art tells of war, birth, hunting, and herding.

Sans Bushmen were hunters and gatherers, living in small mobile groups, taking refuge in caves.

The Bushman tribes have dispersed throughout southern Africa, but many Zulu live in townships nearby where there is an ongoing conflict between the white and black residents, both claiming the land.

Township as seen from R617.

My hiking guide, Keith, hailed from Tanzania. His family, a transplant from Scotland, settled in ‘Tanganyika’ after the Germans lost WW I, and it became a United Nations trust territory under the British Empire. Keith’s family lived on a farm in a rural region of Tanganyika, where his father helped pave the way for British colonists. But after WW II, the British were not interested in maintaining the military outpost. Unrest was so great that Keith’s father returned to England to ask Queen Elizabeth to protect those tribes that helped the British establish their presence. Instead, she told him it was no longer The Empire’s jurisdiction and suggested it best if he and his family leave. So, when independence came to Tanzania in 1961, his family stole away in the dark of night, leaving everything behind with the promise of a better life in South Africa.

Fifty percent of South Africa’s timber comes from KwaZulu-Natal Province. But tourism is becoming popular in the Drakensberg Range. The Giant’s Cup Trail has become the number one running event in South Africa, passing through a World Heritage site of streams and breathtaking views.

The Giant’s Cup in the Maloti-Drakensberg Park.

South Africa has also become a popular destination for African immigrants from Nigeria, Somalia, and Zimbabwe. Unfortunately, a result of the increasing unemployment has been violence. Although rural areas, like KwaZulu-Natal Province, are not targeted as much as urban centers, such as Johannesburg, crossings by residents from the neighboring country of Lesotho are still a source of tension.

From the circular window of a turboprop jet, the view of an endless African plain stretched in all directions—no roads, no people, only beaten down paths from water hole to water hole. Exhausted after traveling for thirty hours, I wondered if I’d be landing in a dusty donkey town or a dream oasis.

I’d heard Maun was once an ugly, remote trading post for big-game hunters and Sans Bushmen. But it outlived the malaria-riddled days with soot-filled lanterns hanging next to canvas-wrapped cots to become a photo-safari jumping-off point in Botswana. Yet it wasn’t the glamour of a safari that drew me there. So why had I traveled halfway around the world?

After getting a restless night’s sleep, I pushed myself out of bed and into the hot, dry air to explore. The first thing I did was stock up at the ‘Old Mall’ where the locals shopped. Women from the Herero tribe, in long flowing, sequin-studded dresses and matching square, flat hats, lugged sacks of groceries curbside where they waited for the next taxi. Many of the Herero tribe had migrated to Botswana years ago when a brutal history saw about 80% of their people exterminated in Namibia by the colonial government.

My bad-ass friend Marenga is the one squatting on the lower left at her sister’s wedding.

Marenga, a bookkeeper, and I met outside the closed library where she, Patience, and Innocent were using the WIFI for free. What an inconvenient time to get a ‘could-not-miss’ phone call.

After about 30 minutes waiting curbside at Old Mall, I got a taxi. That’s when I met Gadaphi. Opening the door, I jumped in the back and told him, “Coca-Cola Road.” Then I pointed in the direction of my place. One could only guess how the cabbies found their way around the web of unpaved roads, dotted with metal-roof or thatched mud huts that sold soda, canned milk, and mobile phone recharge minutes.

“You’re from Maun?” I yelled over the noise of a pickup truck backfiring.

“No. Francistown. Studied marketing. But there was no work there,” Gadaphi answered, with an easy-going resignation in his voice.

Not far from the center of town, we turned left off the asphalt pavement onto a white-sand path where every inch had been scoured for firewood, leaving only the bare ground for chickens to scratch.

“Here’s my cell number,” Gadaphi said when we arrived at my bougainvillea shrouded gate and handed me a ripped piece of paper with scribbles. “Call me if you need a ride.”

From then on, Gadaphi became my go-to driver around town—including the Mission church where they danced down the aisle and told sermons about wayward American women who were misled, got pregnant, then found their way.

Shortly after getting out of Gadaphi’s taxi, I placed my purchases in the metal cupboards and humming fridge, then I struck out on the trail along the river that fronted my home-away-from-home.

Like walking along an ocean beach, my feet sank half a foot for every step in the dry sand.

The sun was just setting, so it was too early for the hippos to surface and purge their lungs with loud flatulent-sounding calls. Still, I walked quickly. Hippos may look like clumsy lumps of blubber, but they’re unpredictable and strike like lightning, making them the deadliest animal in Africa.

On my return to my three-room house on the Thamalakane River, a flock of children raced up, out of nowhere and surrounded me. One of the braver girls, about nine years old, with long spindly legs and a shaved head, pushed in front of the others. Then with a coy innocence that fooled no one, said, “Give me pula.”

“Sorry, I have no money,” I told her truthfully. It was inside the lushly landscaped AirBnB.

Eyes flaring, she yelled in disbelief. “Aren’t you American?” She waited for me to find some coins in my pocket but I had none. Disappointed she said, “My name is Bontle—it means beautiful.” And she was with cedar-brown, silky-smooth skin. But beneath her lovely exterior, I saw a tough little spirit.

A woman’s voice called out from a distance. Wide-eyed with alarm, the children picked up their firewood and scurried off down a different path.

“Goodbye, my friend,” the bald Bontle yelled back. Thus began the first of our daily greetings.

Several weeks later, on my weekly grocery shopping excursion into town, I stopped by a small, sparsely furnished office with an overhead fan, to get a quote on four-wheel-drive car hire (rental). The agent and I talked about the 4×4 truck, what the road was like to the reserve where I’d be driving it in about a month, and other things. I learned he grew up in Maun, went to senior secondary school, and was the oldest son in his family. I told him I owned a four-wheel drive back home and had driven it in the mountains.

“When we return from the reserve, I’ll give you my 20-liter gas can,” I told him.

The one I needed to buy because there was only one gas station every four hours. That way, he could ‘loan’ it to other tourists for a fee and maybe not notice any scratches on the truck when I brought it back.

He smiled knowingly.

After we shook hands, I stepped out into the hot sun and meandered over to a cluster of trees where taxi drivers hung out. With no bus service in town and few private vehicles, cabbies always had work. Whether it was enough to pay the bills was a different issue.

Next to the dirt parking spot, safari jeeps with high-riding, nine-seater, canvas-topped 4x4s and tourists with wide-brimmed hats sporting tailored clothing waited for their groceries to be loaded. They were going on a guide-driven safari, where everything was taken care of for them, from tents to candle-lit drinking binges. And hopefully, a life-long experience worth every cent of it.

A week later, my friends and I flew into the Okavango Delta on a six-seater plane. Under us, a swampy archipelago of tear-drop-shaped islands grew then shrunk, as a ribbon of Angola’s flood-waters drowned the connecting land bridges. The network of branching paths from landmass to landmass, beaten down by wild game, reminded me of an old saying, ‘All who wander are not lost.’ Again, I wondered, “Why was I here?”

Just before we touched down, a man nonchalantly chased baboons and warthogs off the landing strip. From there, a boat carried us through undisturbed World Heritage marshland to our lodge.

Within the pristine swamp’s borders, there were no barriers. So Elephants tromped between tents while crocodiles sunned themselves at the base of boat launches.

Sexual boundaries were also ignored, and infection by HIV was rampant.

“How many weeks at a time do you work in the Delta?” I asked an apron-clad woman as she prepared a ‘stuff-yourself’ white-tablecloth buffet.

“My shift is six weeks on the job, two at home.” She gave me a hesitant smile. “Wish I didn’t have to be away from my little girl so long. But many from Maun work out here. We need the money that Delta jobs pay.”

It struck me such an arrangement was a recipe for trouble when a wife or husband stayed away from home for too long. And I noticed one of the bush guides give her a long, satisfied look. She scowled at him. Like many Botswana females, she had fully endowed buttocks, something her co-worker seemed to find pleasing.

Later that night, with the soothing sound of the delta waters lapping against the lodge’s wood pilings, the conversation grew loud and lively. Khaki-uniformed men carrying perspiring bottles of wine wrapped in white cloth filled our glasses to the brim.

“Did you know Botswana has the highest incidence of HIV and syphilis infection in all of Africa?” a tourist asked.

“That’s statistics,” our guide answered, unfazed. “Botswana just does a better job of collecting data than our neighbors.”

“Aren’t you afraid of getting AIDS?”

“A man will be a man,” he chuckled. “Everyone dies eventually.”

But do all your partners think that way, I wondered. And for the rest of our stay, I watched their sexual dance play out and marveled at the wildlife.

A month later, the Monday arrived for me to pick up the 4×4 and start our self-drive safari. I was nervous, never having driven through drifts of sand before with animals crossing at will.

We’d rented a tent on stilts in Khwai, a land development reserve run by local villagers.

The only thing missing was a guide. But it was peak season, and everyone was booked. So I hired the caretaker of our rental, T-man, a local Sans Bushman.

Immediately after we arrived, we drove down an animal trail along a stream, twigs slapping the truck, blinding me at every curve.

Twilight cloaked the horizon with a ruby red glow. I was exhausted after the six-hour drive from Maun but drove on.

“Closer,” T-man urged. “Go farther down the path.” His voice was monotone, but his body was tense.

Along the stream, elephants ripped clumps of long, waxy leaves out of the water, then ground them into a pulp. It would be their last meal of the day because the predators had them on the run at night.

Suddenly, deep, from within the nearby bushes, a cacophony of bickering birds broke out in alarm. The tall upland grasses on our left rustled. At the sight of a leopard, we stopped. It was time for her to eat.

“I’m going back to camp,” I said and made a three-point turn in the sandy path. Call me a wimp, I thought. But there was no way I’d get stuck in that saturated quicksand to become her next meal. The light-brown bushman pulled his knit cap low, then crossed his arms. He’d never driven a car before and didn’t understand we could get stalled. And I wasn’t getting out of that truck to dig us out.

After a relaxing stay in Khwai, we returned to Maun. Weeks passed. I found a licensed guide and this time, when I took my daughter to Khwai, he drove to the reserve. I realized there were some things I shouldn’t have cut from my budget—like a driver who understood the bush. A friend suggested I call the Land Trust, who told me to contact someone they knew, who had me call someone else, who knew of someone I really should hire. The guide was a stranger to all of them, and I’d be spending twenty-four hours a day for seven days with him nonstop. Eventually, we met. He wore a leather safari hat, was tall, limped on his left leg, said his name was Rogers, and I was supposed to trust him. So I did.

Rogers had the bush under his nails, doused through his hair, and cemented in his soul. He told me stories of when as a child he had trailed through the village behind his uncle, a man of respect, who had rallied the tribes to support Sir Seretse Khama when he ran for president instead of remaining a bush king. Certainly a gentleman by any definition, Rogers told me while I was unloading a cooler from the truck, “I have a wife and know that women are strong but sometimes their pride won’t let them ask for help.”

One night after we returned from our game ride, I stood by the open-pit fire at the edge of our tent-on-stilts, cooking chicken while the others relaxed on the balcony. I heard rutting calls from some antelope in the trees nearby. Shortly after, they were replaced by a hollow whistle. Then there was nothing—until Rogers came rushing down the stairs.

“What are you doing?” he asked frantically, dusting the area with the beam of his flashlight and clutching a knife in his other hand. “Hyenas have come.”

Rogers explained how several hyenas had smelled the sizzling chicken fat and were prowling only feet away. So upon catching sight of them, the antelope warned each other with their whistles to flee. Communications among animals in the bush seemed so intuitive. Why was it hard for humans to understand each other? My thoughts went to T-man.

One day, when Rogers returned from visiting T-man in his hut, he told me, “T-man and his wife sit in the same room for hours and don’t talk. They don’t use words; instead, Bushmen use their bodies to speak for them.” I couldn’t imagine passing a night with no computer, no phone, no books, and no conversation. It was as if the bushman had a sixth sense that I couldn’t perceive. I thought of the game rides we’d gone on with him. He could have been shouting at me with his body talk, but I heard none of it. I’d become too dependent on words, text, and emails to see there were other ways of connecting.

A couple of days later, T-man’s wife shuffled over to our shared water spigot and filled a plastic jug. She looked at me but said nothing. Still, I felt her unspoken nudge.

“I saw you getting off the bus yesterday. Were you returning from work?” I asked.

“No, from Mababe,” she answered.

“You go there often?” I remembered the village as the only petrol stop for hours.

“My son is sick. He has been crying every night for days. We saw the doctor, but he had no medicine. So he told us to come back another time. But we don’t know when they’ll get the pills our baby needs.”

I’d seen the baby’s runny nose and rheumy eyes but thought it was nothing more than a cold. The thought of the antibiotic pills back home that were thrown away once the expiration date passed, even if they were still good, made me angry. Pills that wouldn’t be shipped to Africa because someone could be sued. Pills that could save a baby’s life that were flushed down the toilet. Before we returned to Maun, hoping to make amends for not hearing the caretaker’s body language on my first trip, I set some money aside in an envelope for their baby. For T-man’s pride and joy. For his wife’s love of her life. For naught, if there were no pills to be bought.

Finally, the time came for me to leave Botswana. I took my last walk along the river.

“Hello, my friend.”

I turned to see Bontle and her pack of friends rush up from the water’s edge.

“What have you brought me today?” she asked.

I’d taken to handing out bouncy balls and lollipops, but I had nothing that day. So I said, “Let me show you something instead.”

I unslung my binoculars, then gave them to her. “Look through here,” I said and pointed at the two rubber-rimmed eye-pieces.

With a look of smug satisfaction, she put them up to her face. But her expression quickly changed to doubt. Then as if the binocs were cursed, she held them out for me to take them away.

“My turn,” her brother said. One by one, the binoculars traveled from child to child. Each of them getting more excited, their high-pitched voices babbling nonstop. Finally, it reached Goitse. A quiet girl, taller than the rest.

Hesitantly, she raised the binoculars—backward—with the larger lens to her eyes and saw nothing.

I turned them around. “Try again.”

Goitse grasped the binoculars limply at first, slowly scanning the ground in front of her, where a brown and white cow grazed on the edge of the floodplain. Quickly, she stepped back as the viewfinder leveled on the gentle giant’s dark eyes. Under the lenses, they must’ve been as large as two moons. From there, Goitse tracked an African hornbill flying between the trees, cackling and wobbling on branches in a drunken stupor.

As she swung the binocs skyward, my eyes followed her path up to billowing clouds that morphed into mythological gods. Then dreamlike, the sun soaked the white pillows in the sky.

When Goitse pulled the lens away, I was struck by the naked emotion on her face and wonder in her eyes.

Finally, I realized why I went to Botswana. I had, as they say in Swahili, gone on a safari, but not to see wildlife. Instead, I journeyed inward to rediscover the magic in life that I had buried under layers of knowledge. Thanks to Goitse, I saw dream-like illusions in the sky by looking at the world through the eyes of a curious child.

Kingdom of the Sky – Lesotho’s entire country is above 3000 feet or 1000 meters.

Lesotho, a Commonwealth Nation, became independent from the United Kingdom in 1966. Surrounded by South Africa, most of Lesotho’s land mass is in highlands.

Photo from South Africa, Drakensberg Range side.

Driving up the switchback road through the Drakensberg Range to Sani Pass is not for the faint of heart.

Sign warns of driving beyond that point without 4-wheel drive. It’s no joke.

The stark beauty is visceral.

Nestled between the Maloti and Drakensberg Mountain ranges, only 14% of Lesotho’s landmass is arable. And of that, only a portion is accessible to be farmed.

If you’re brave enough to drive to Sani Pass yourself, congratulations. I chose to hire an experienced company in Underberg.

I could not speak his language, so I could not learn if his instrument was made from a plastic bottle, animal sinew and weather wood, or what.

I found Lesotho interesting in that much of its natural resources are exported, leaving inadequate resources for its own population. As a comparison, South Africa’s GDP is 4 times greater than Lesotho with most of Lesotho’s poverty in the rural areas.

Lesotho produces 100% renewable hydroelectric power, but that’s sufficient for only 50% of its need.

On top of that, it sells some of that power to South Africa, leaving insufficient domestic water, which is exacerbated by an inconsistent climate.

So what does a country do without a constant supply of tourists or arable land? Antelopes, elan in particular, are typical targets.

Poaching on South African land is not unheard of, even though it’s illegal. Elans in particular are targeted.

But how tempting it would be to cross the border when the other side of the rain shadow is so promising.

Copper, Livingston, Victoria Falls, and a history of British Rule

I got a cheap puddle-jumper out of Maun Botswana after a friend said, “I’m going on a self-drive safari to Chobe and Victoria Falls in Zambia. Do you want to meet me in Kasane? I need to know today.”

From that trip, I learned to leave plenty of time to wait if you’re going to the Botswana Zambia border. So we chose to leave our vehicle in Botswana and hired drivers to take us to and from the border.

I found it interesting that they required everyone to spray their shoes so as not to track unwanted seeds or infections across the border on the Botswana side. Zambia didn’t have the same requirement. I think the hoof and mouth disease that hit the cattle/water buffalo is what prompted such attention. Another difference was Zambia required visas to be paid in dollars. So always bring plenty of dollars to Zambia or you may end up paying a lot more.

After passing through customs, we got in line and boarded the local public ferry on foot.

Standing room was okay since travel across the Zambezi River at this point didn’t take long.

But on the Zambia side of the border, a convoy of 100 soot-belching, copper-carrying semi-trucks waited to be loaded onto the flat-bed boat, one at a time. Then they traveled by land down to Durban, South Africa. The size of the ferry made the wait intolerably long for those crossing from Zambia.

I asked one of the truckers why travel in a convoy knowing there would be a horrendous wait to cross the border.

The driver said, “It’s a shorter wait than getting hijacked at gunpoint. Convoys are the surest way to go.”

This delay also gave the Zambia day laborers a chance to drum up work, something the Zambia-poor government created after giving enormous tax breaks to the privately-owned mining companies.

We maneuvered our way to our connecting ride through a pack of restless laborers.

“You want a ride?”

“Buy my bracelets. They’re made from real copper.”

“You need tomatoes? Onions?”

It made me realize the ecotourism on the Botswana side of the river was doing more than just providing tourists with an exotic backdrop for Christmas cards. Their money was trickling down to all the Tswana.

En route to Livingstone, I saw hectares upon hectares of drought-afflicted branches. What do you do for a country that has such little arable land of commercial value? And those parcels that do produce, are privately owned with next to nothing trickling down to the little guy. I’m not sure if this is a relic of the British social structure, but Zambia could make more of showcasing its wildlife and natural resources to generate more revenue.

At any rate, I hoped to see some of the British-era architecture in Livingstone, a town named after a Scottish missionary–explorer–doctor who was sent down to Anglicize the region. A man with a flawed character, Livingstone did much to further the world’s knowledge of medicine, African geography, and Britain’s Imperial future in Africa. Unfortunately, in the end, he was killed by a lion while struggling with malaria in the bush on his last exploration.

During my short trip to Zambia, what surprised me the most was a depiction at the Livingstone Museum of the African culture pre-1800 and post computer era. It was as if this part of the world never saw the Renaissance, the Industrial Revolution, or any World Wars. Instead, from tribal hunter-gatherers to cell phone carriers, the South African culture evolved rapidly in a short period of time.

Once we got outside Livingstone we headed to Victoria Falls. There, on the deafening path to the falls, I overhead a tourist say, “Victoria Falls is just another waterfall.” To me, that was like calling the Grand Canyon another hole in the ground.

It’s amazing to see the meandering flow of the Zambezi River right before it drops over The Falls.

I asked the seventy-three-year-old bible teacher traveling on the self-drive safari with me, “How tall are the falls?”

“Three hundred? Four hundred feet tall,” she guessed, shrugging her shoulders. Below us, the Zambezi River boiled as the falls gushed over the rock shelf a mile wide.

“I saw them years ago from the Zimbabwe side when it was still Rhodesia,” she shouted

Zambia was part of the British Colony of Rhodesia until independence in 1964. But unlike Southern Rhodesia, where a 15-year civil war (The Zimbabwe Bush War of Liberation) kept it from being totally free from white rule, Zambia (Northern Rhodesia) became a free nation immediately upon independence from The Empire.

“Why did you leave Rhodesia? I asked.

“The Bush War. We lived on a farm. It wasn’t safe to stay.”

“I heard it was a nasty civil war,” I said. “Fighting in the cities and all.”

“Heavens, no.” She looked surprised. “It was the farms the guerrillas wanted. It was the farms they attacked.”

I asked her if her farm had been under fire. She said, “No. Every night we’d radioed the other farms to make sure everyone was okay. But we always got word from the Reserves before the guerrillas attacked. ”

“Reserves?” I asked. She went on to explain, “Husbands, like my Jim. The government sent them out for six weeks at a time. They put black paint on their faces. Wore old clothes. Couldn’t bathe for weeks because the guerrillas could sniff ‘em out.”

“What did you do when he was gone?”

“I stayed home with the children. She looked into the distance as though reliving the past. “One day after dropping the kids off at school, a group of black teens blocked the whole street. I stopped and waited for them to let me pass. But instead, they walked toward me. I didn’t know what to do. So I drove into the ditch and around them, then gave them an unladylike finger as I sped away.

“Must’ve been scary,” I said.

She nodded. “All us mums with little ones kept personal weapons on us, and the older boys carried rifles everywhere.”

The image of schoolboys in starched white shirts and blue ties toting guns through the academy’s halls came to mind. They had most likely aimed those rifles at people they knew—people who had worked on their farms—people who, like lions on the plain, were roaming the grasslands at night.

“We made it out of Rhodesia to South Africa. But we had to leave everything we owned behind. I can’t say South Africa was much better. Shortly after we arrived, a black teen broke into the house. Stabbed me in the back six times.”

At the Knife Edge Bridge, we stopped speaking, overpowered by The Fall’s thunderous sound.

Then we watched a bungee cord jumper leap from the metal-arched 400-foot Victoria Falls Bridge in the distance.

Tourists! I thought. Risking their lives for what? Such an insult to these people who had been beaten down by so many years of civil war. My thoughts went back to the jobless men at the border crossing, men with no hope for the future. It was no wonder they had post-traumatic stress in their eyes. Then I remembered Wisdom, a Zimbabwean I’d met in Botswana.

I’d met Wisdom on one of my daily walks along a tributary to the Thamalkane River.

“What are you making?” I’d asked the slender, Black man in blue overalls digging a two-foot-wide ditch.

He greeted me with a bright, comforting smile. “This will be a fence,” he said and pointed at the one on the next property. “Like that—with lights.”

“Do you always work alone?” I asked.

“No. The others had to go. I live just over there.” He nodded at a concrete building no bigger than an eight-foot-square shed. “I told them I would finish up for the day.”

“You have a different accent,” I said. “Where are you from?”

“Zimbabwe,” he answered.

I was puzzled. “I thought things got better for Blacks after The Bush War.”

“I could not find work there.” He looked down as if gathering his thoughts. “I cannot say The War was wrong. Before the fighting, it cost us almost half our monthly salary for transport. The Whites would not listen when we complained. But after The War…Well, we should not have wanted it all. We should have worked with the white people. Learned how to farm their land, use the equipment in their factories. Then shared the country. Now it sits broken, so I must travel here to feed my family.

“I’ve heard the local Tswana say Zimbabwean laborers work too hard—show them up.”

He shook off the compliment. “I do what I must and go wherever there is work.” Then he lifted his shovel and continued to dig. As I waved goodbye, I thought Wisdom seemed to be precisely that, wise. It was as if his soul had chosen his name.

NORTHERN SPAIN – Barcelona and Walking the Camino de Santiago

Whether you land in Madrid, fly into Barcelona, or walk across the French or Portuguese border, make sure you leave time to do more than just walk the Camino. I flew into Barcelona, a city with something for everyone.

A visit to Guell Park is a must. From parrots to Gaudi’s house to Romas dancing flamenco, it’s magical.

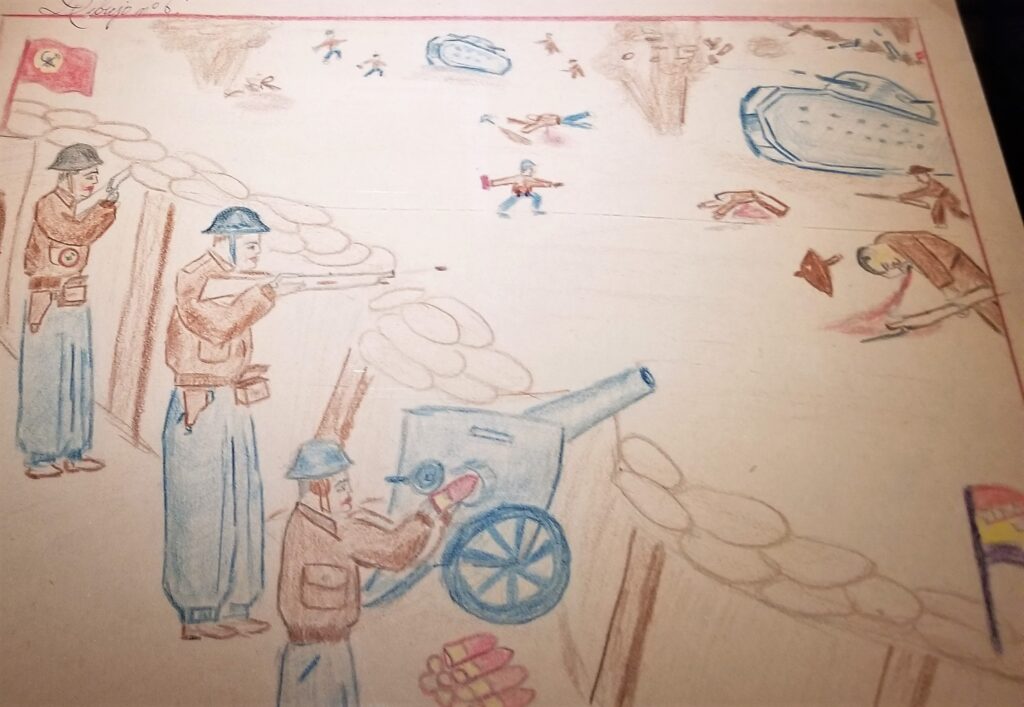

And at St. Philip Neri church, there are reminders of a civil war, less than 100 years ago.

Walking the Camino de Santiago Compostela

There are seven well-established routes of St James, otherwise known as the Camino de Santiago. The Camino de Santiago Francis is about 500 miles long, starting in the Pyrenes and going to Santiago Compostela. It’s a very personal journey. The best way to do it…is your own way.

Most people walk The Camino de Santiago Francis in a month, but you can break it up into several trips. That leaves you with a reason to return, to finish the hike and hear more stories from around the world.

Imperial Splendor – Museums, Ornate Windows, and Onion-Dome Churches

We all know Russia is huge and very diverse. And making reservations for places, like the Bolshoi, can be daunting if you don’t speak Russian. But I learned the best way to get to know the people, is to find a room at an Airbnb rather than rent a flat, then use the phone translator to chat. So, even though most Russians don’t speak English, it’s easy to get around. And one place I always go to get the lay of the land is the grocery store. Just hop on the nearest metro, which can be very deep in Russia.

Moscow’s subways are up to 55 meters underground. St. Petersburg’s go down 86 meters, 27 stories.

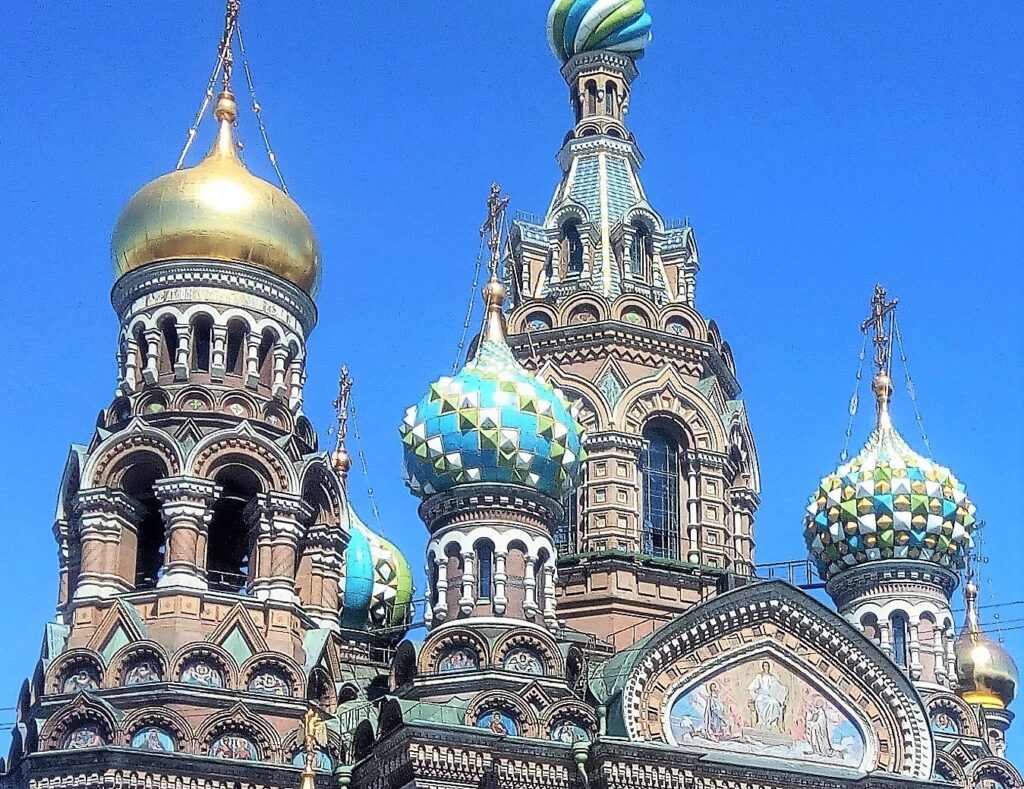

St. Petersburg – The Venice of Russia

St. Petersburg is known as the Venice of Russia with canals everywhere. A delightful place to visit in the summer, even if it’s too bright outside for the street lights to turn on until midnight. Then they turn off two hours later. And it stays dark too long in the winter.

But any time of the year, there is creative magic in the air, as if Russians never grew up.

Grand Market

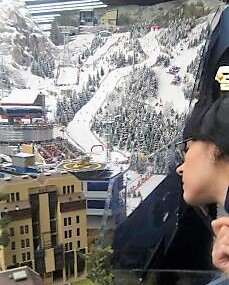

Grand Market is a private museum displaying a slice of life in Russia. The computer-operated miniature model of everyday life depicts mundane aspects of living, like shipping operations, as well as recreational activities, like winter sports and scenes of military glory. It’s almost an indoctrination of Russian values, and you can see pride on the faces of all the Russians, old and young, who visit this museum.

There’s great artistry everywhere. The buildings, music, Faberge eggs, and the young women dressed to the nines, make fashion-conscious connoisssiuers in Paris, Milan and New York look twice.

Built in the early 1700s, and known as the winter palace, the center of the Hermitage was home to the Imperial Family until the revolution in 1917. In 1779 Catherine the Great acquired 204 pieces of art from the Walpole collection then expanded the palace, in the Russian Baroque style, to house the artwork. The Hermitage is just one of many excellent museums worth visiting in St. Petersburg.

You can catch a hydrofoil on the Neva River, near the Hermitage, to get to Peterhof, one of the Royal Family’s summer palaces.

Peterhof

Also built in the early 1700s, and only forty-five minutes by boat west of the Winter Palace, is the Summer Palace, Peterhof. The extravagance helps the visitor understand why there was a revolution.

Veliky Novgorod – Western trading front on the Volkhov River

The land between St. Petersburg, the second-largest city in Russia, and Veliky Novgorod, one of the largest European cities in the 14th century, is sparsely populated—and probably very cold in winter.

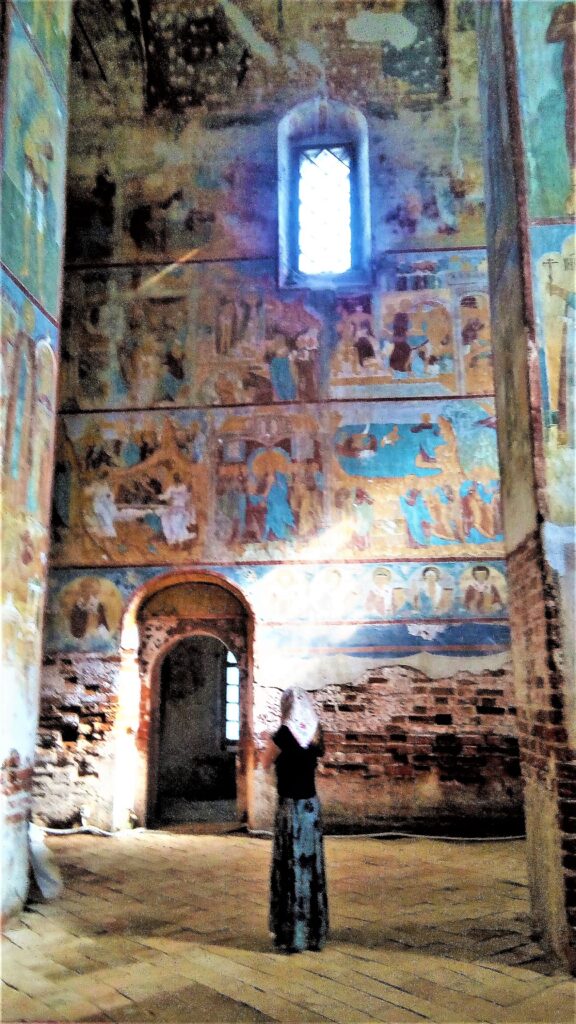

One of the western-most cities in Russia, Veliky Novgorod’s art shows how greatly it suffered during what the Russians call The Great Patriotic War, where 20 million Russians lost their lives.

Vitoslavlitsy, an open-air museum, is a twenty-minute bus ride from Veliky Novgorod. Take Bus 7 to see the centuries-old Slavic wooden architecture that was moved from other villages in the region, then reconstructed on-site to show what ancient Russian life was like.

Built in 1030 CE, St Georges Monastery, about 5 km south of Veliky Novgorod, is said to be the oldest monastery in Russia.

Moscova (Moscow) – A city well worth walking – then take the metro home.

A train is the best way to get around the rural areas. But the stops are limited. So, you may need to hire a car to take you from the station to the town you want to visit. The trip to Moscow goes through wooded villages to concrete high-rise apartments in the country’s capital. I was told there are no homeless in Russia because everyone is given a place to stay, even if the kitchens are so small that you can touch the sink with one hand, the stove with another, the table with one foot, and the door with the other.

Museums, music, and ballet are the lifeblood of Moscow.

Located in an unassuming building near the Pushkin Museum is the Art Gallery of the European and American Countries of the XIX-XX Centuries. There are paintings from Picasso, Van Gogh, Gaugin, Matisse, Renoir, and other famous masters that I’ve never seen in other galleries. It’s OUTSTANDING.

If you want exquisite sound, go to the Tchaikowski Conservatory, not the Tchaikovsky Concert Hall. But catch a taxi early. The traffic in this area is horrendous.

And where else but the Bolshoi can you see a dancer leap across the entire stage on bulging frog legs.

When most people think of Moscow, the Kremlin comes to mind. But many towns have Kremlins, or citadels within a town housing the administrative offices, ruling entities, and churches. Moscow’s Kremlin has five palaces and four cathedrals, all surrounded by its red brick wall and towers.

Golden Ring In 1967, after journeying northeast from Moscow to Yaroslavl then down to Suzdal and Vladimir, traveling in a circle back to Moscow, Yuri Bychkov, an art historian, noted the area’s unique Russian architecture from the XII-XVII centuries and aptly named the route the Golden Ring. There are day tours from Moscow to the Golden Ring, but I chose to hire a car for long-distance travel, then took buses locally.

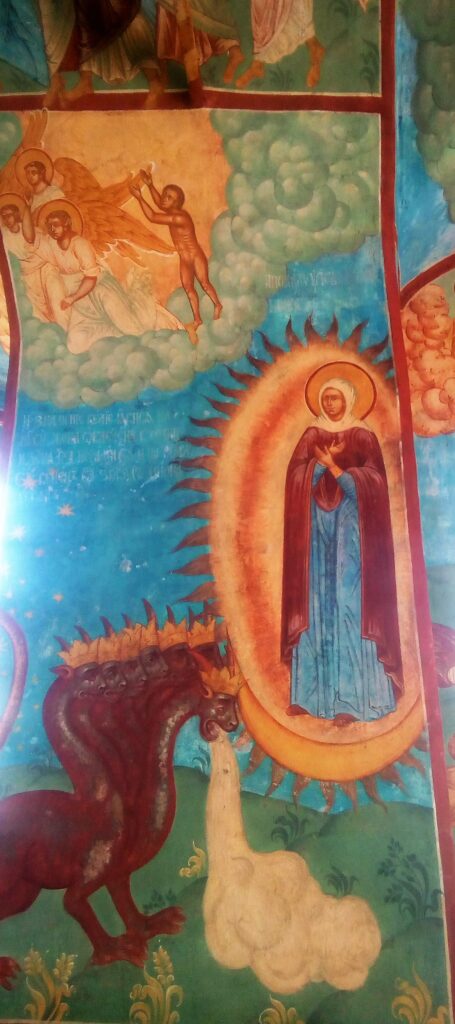

Yaroslavl – Located on the Volga River, Yaroslavl was the defacto-capital of Russia from the time of the Polish invasion in 1608 until 1612, when a peasant army liberated Moscow. Throughout time. Yaroslavl has suffered 13th-century attacks from the Mongol Golden Horde, received visits from Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century on his pilgrimages to the Spaso-Prebrazhensky monastery, and is known as the City of Churches and monasteries frequently visited by cruise boats on the Volga River.

Vvendenskiy Tolga Monastery is really a convent on the left bank of the Volga River, downstream from Yaroslavl. It was founded in 1314 CE.

Further downstream, Tutayev, a 14th-century town of 42,000, is split in two by the Volga River. Most inhabitants live on the right bank. But picturesque homes and churches on the left bank are worth the visit.

I called the Voskresenskiy Sobor the ‘hands and knees’ church. Built in (1678 CE) on the right bank in Tutayev, you get on your hands and knees when you enter, then crawl along a tunnel to reach the end, where you kiss a holy cross.

Suzdal – Sleepy Village in the Golden Ring

Most of the time, I had to use my phone translator to speak with the locals, speaking into it then turning it around for the Russian to see the translation in their language. One person, a retired soldier, surprised me with his view of the US. I told him that while I was growing up, we had air-raid practices at school in the event we were bombed by Russia. Whenever we heard sirens, we’d drop to the floor then crawl under our desks. I asked him whether Russians had a similar drill in the event of an attack by the US. He said, “It’s the Germans we worry about not the Americans.”

Kazan – Where west meets east and Muslims outnumber Christians.

If you don’t have much time to spend in Kazan, check all the transportation schedules as soon as you arrive. Don’t be like me, and assume the hydrofoil to Bolgar is in operation. The boat was down the week I visited Kazan. And not only was it difficult to find a car to take me down there but with a shortage of hotels, I would have needed the driver to wait while I visited the site.

The weather in Russia is brutal. St Petersburg’s temperatures range from 21 to 65 degrees Fahrenheit. Moscow’s climate goes as low as -18 and as high as 65 degrees Fahrenheit. While Kazan goes down to -14 and up to 88 degrees Fahrenheit.

In Kazan, I took a room with a family at an Airbnb. As is the case with many Airbnb room rentals, one family member gives up their bedroom for the guest and sleeps in the living room. In Kazan, it was the grown daughter who lived with Grandma and Grandpa, in a high-rise apartment, and all the relatives from out of town who wanted a place to flop—or gawk at the foreign visitor.

Since I couldn’t get to Bolgar, I spent more time than expected chatting with Grandma. A warm-hearted, charming woman who spoke no English, she made the same soup every day-onion soup. With the help of the translator on my phone, I learned she had a crush on Putin, loved soap operas, and couldn’t believe my teeth were real. So, she opened my mouth, as though I was a horse, and checked for herself. Satisfied, she nodded her approval.

During the Cold War, all sites of religious worship, not just Christian churches, were closed. So, her family held clandestine Islamic services in their home. There, as a girl, she taught the Muslim Tartars how to speak Russian, since jobs were not available to those who spoke only Tartar, even though Kazan was predominately Tartar.

She had turned 75 the week before I came and probably prepared the feast herself for her entire extended family. When we think of Russians, it’s hard not to picture soldiers, Olympic athletes, or politicians. We forget about the majority of Russians, proud of their heritage, full of dreams, and like Grandma satisfied with her life of giving. As I was leaving to catch my ride to the airport, she ran out the door after me and solemnly gave me a bar of soap. Since then, I bring a bar of soap on all international trips, to give to the new friends I make along the way.

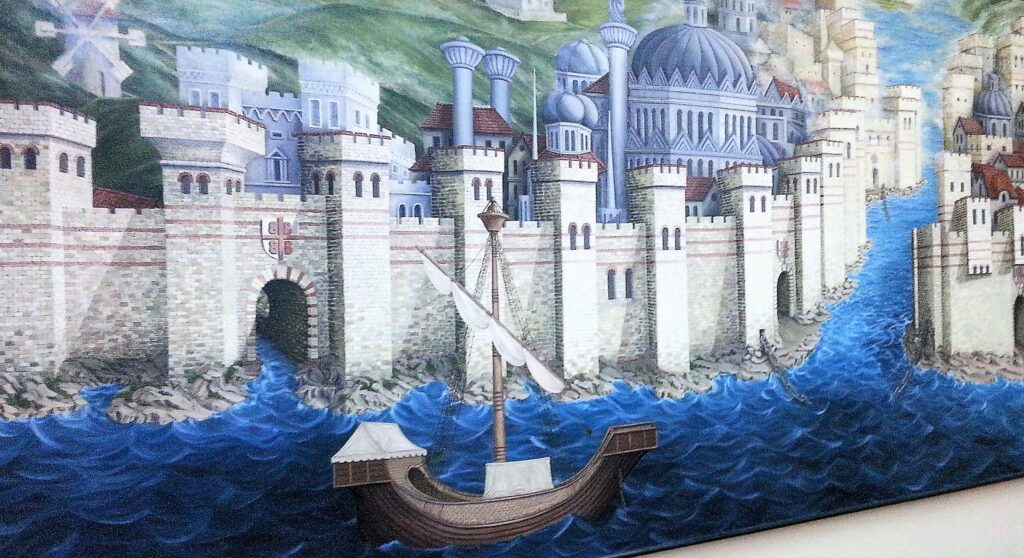

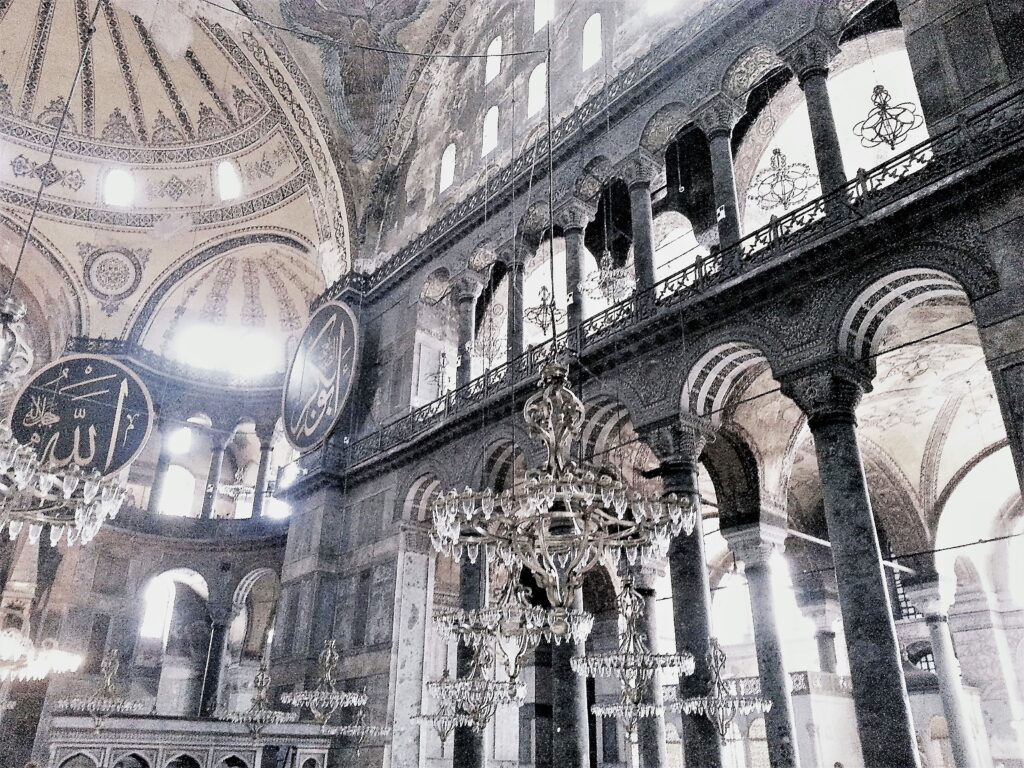

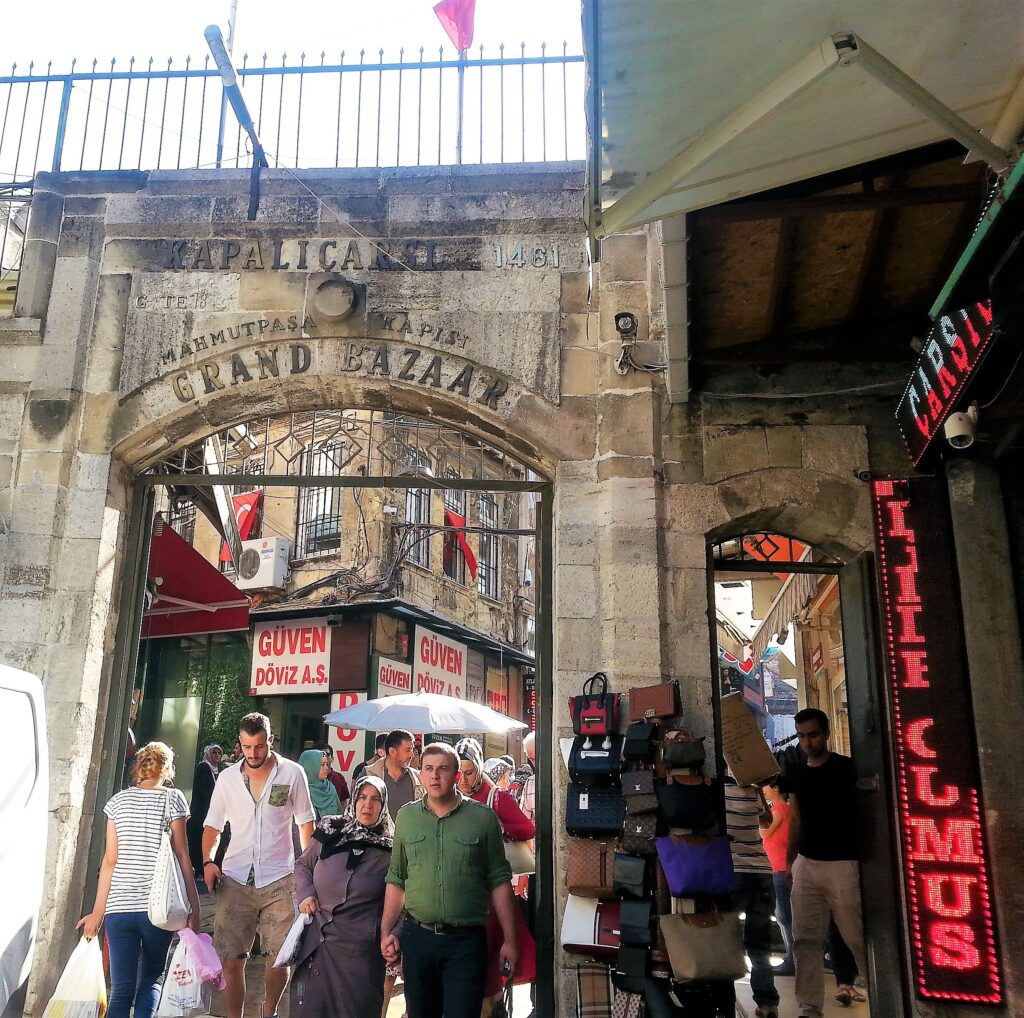

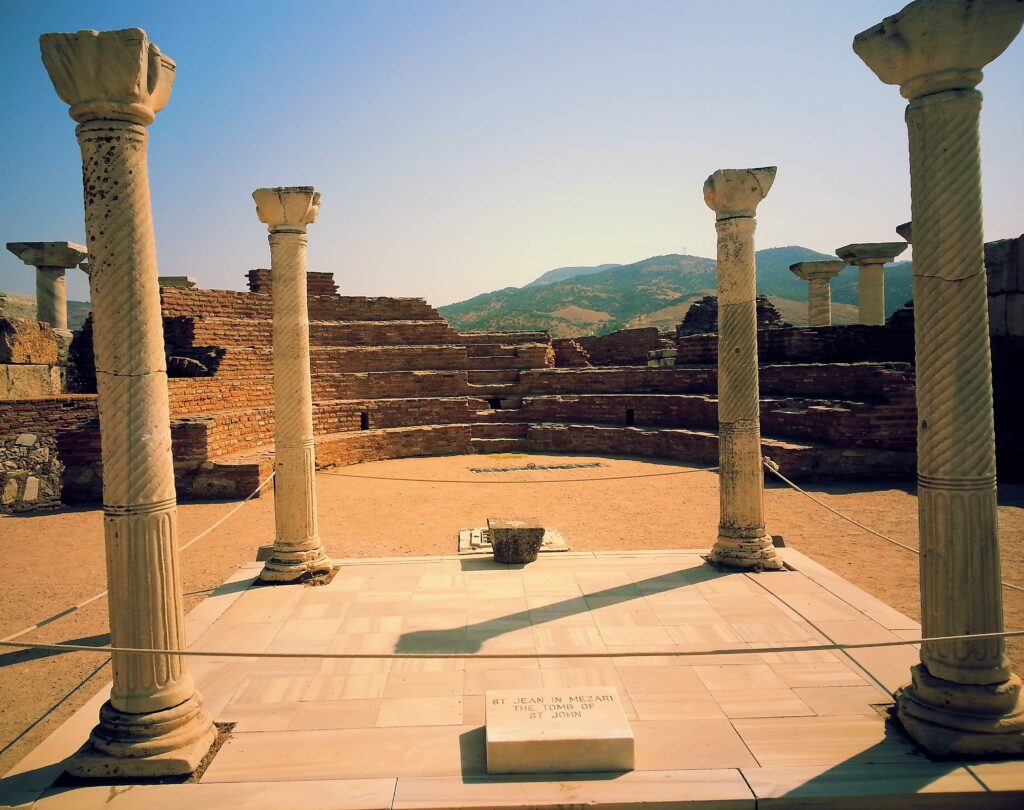

Istanbul – City of Seven Hills worth walking up and down.

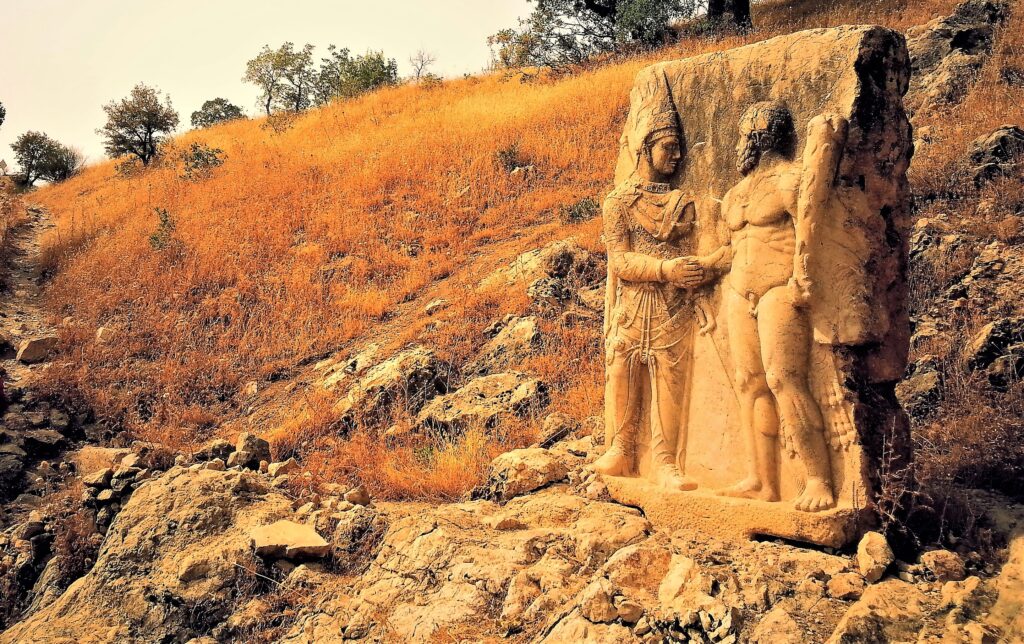

Processional colonnade at Pergamon. The biggest city in the region during the 2nd century BCE.

Following the map in Kate Clow’s, The Lycian Way, Turkey’s First Long Distance Walking Trail, we covered only a portion of the -550 km hike.

We were going to fly into Diyarbakir to visit the Coptic churches in the areas around Batman, Midyat, and Mardin, but tensions at the Syrian border got out of control so we changed our flight to Malatya. Upon landing in Malatya, I noticed all the fighter planes on the tarmac but figured they were part of the Turkish military. The next day we drove down to a place outside Mt. Nemrut. At midnight I heard the rumble of planes overhead. The next day we learned of the bombings in Syria. That’s when the great exodus from Syria began.

When visiting Ireland, an island with castles, churches, and conflict, you can’t ignore the history.

1845-1852

It is said, Ireland’s greatest export is its people.

1920s

In 1921, the Irish successfully won independence from Great Britain, creating a Catholic Irish Free State in the south and a predominately Protestant Northern Ireland. The partition of the island (Gaelic: críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was based on 17th-century British colonization. The six counties in the northeastern and northcentral portions of the island, Northern Ireland, remained under British rule, whereas the remaining 26 counties in the northwest and south became the Republic of Ireland. The intent of the partition was to eventually reunite the north with the south, but unification has eluded the island.

1960s-1990s

The Northern Ireland Conflict, or The Troubles (Na Trioblóidí), started with the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. In Northern Ireland, an equal rights campaign to end the discrimination against the minority Catholic/Nationalists (Republicans) by the majority Protestant/Unionists (Loyalists) was violently opposed by the Unionists. Loyalists supported the Protestant United Kingdom to maintain rule, but Republicans complained of housing and job bias by the government.

Republican Civil Rights marches were repeatedly attacked by Protestant Loyalists and the Royal Ulster Constabulary, an overwhelmingly Protestant police force. In the predominately Catholic communities of Belfast and Derry (legally Londonderry), there was fierce fighting and rioting. Homes were burned in Belfast around Clonard Monastery, and many were killed, including the Clonard Martyrs.

The Provisional IRA (Irish Republican Army (Óglaigh na hÉireann), known for car bombings and revenge killings, was an Irish Republican paramilitary organization that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, facilitate Irish reunification and bring about an independent, socialist government. On Good Friday, April 10, 1998 agreement was reached with most of the political parties on how to rule Northern Ireland. Since then, the IRA is considered an illegal terrorist group.

Yet explosive hints from the past are seen everywhere. Such as the innkeeper with an Irish mother and Palestinian father or when I asked for directions to Derry and a young man corrected me with, “That’s LONDONderry.” In Northern Ireland, battle lines are still drawn.

NORTHERN IRELAND – A land of ghostly beauty

SOUTHERN IRELAND. Land of Faries, Iron Age bogmen, 6,000 year old Neolithic Cemeteries, and Yeats.

If you are a seasoned traveler in Southern Africa, you know if you want to go to Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, or South Africa.

Victoria Falls Zambia

Sani Pass, Lesotho

Drakensberg Range, South Africa

If you have decided upon Botswana, you may have already chosen between Chobe, Savute, Khwai, Moremi, Okavango Delta, Makgadikgadi Pans, Nata bird sanctuary, Elephant Sands, Tshildo Hills or the Kalahari.

Red Lechwe, endemic antelope, in Chobe National Park

Wild Dogs, Khwai Botswana

Leopard Moremi Game Reserve

Yes, they do cook with cockroaches in Thailand. They use the body fluid as a spice.

To many westerners, the use of insects seems primitive yet Bangkok is anything but that with skyscrapers and all the modern conveniences of any other developed country.

Having said that, go to market and you can choose the type of blood you’d like to cook with – a vampire’s fantasy.

Vegetarians are also in tenth heaven with a wide assortment of green vegetables at the market.

You can’t be inhibited if you want to experience Thai foods – even if they look strange to western eyes.

But they taste like nothing you can get back home. So eat well in Thailand.

I took a cooking class at the Blue Elephant Restaurant rather than get caught in the crossfire of the political unrest at the time.

The Blue Elephant class wasn’t cheap but it was worth the tour of the market, five-course meal, and ambiance.

Juxtaposed between new high rises and the ferry launch in Bangkok, you can find reminders of the old colonial presence, such as the historic East Asiatic Company headquarters.

Took a local commuter boat on the Chao Phraya River where dragon boats share the waterway with modern ferries.

And long-tail boats transporting goods are seen passing famous sites such as Watt Arun.

Less famous but very impressive is the cable Rama VIII bridge.

What caught my interest during the time I was in Bangkok was the struggle between the Peoples Democratic Reform Committee and the Pheu Thai party run by Yingluck Shinawatra, whose brother, the former Prime Minister, was in exile due to corruption. Hundreds of thousands of demonstrators lined the streets, resulting in traffic jams, blocking access to the airport, killings, and eventually a coup d’etat by the military. Like so many other trips I’ve been on, I was able to catch a plane home to my secure, comfortable life…for now.

The UNICEF poster shows what is happening in Myanmar – children are fighting a war rather than attending school. There is a struggle between the government, who wants to claim the land, and the people, who want to harvest the gold, jade, teak, and opium as they have forever.

I bought a ticket for a first-class sleeper on the train from Mandalay to Myitkyina, knowing the Kachin and Shan guerrillas were fighting in the area, and it was possible the military might block my travel.

Along the way, I saw the presence of Buddhists openly challenging the Muslims.

The countryside looked quiet and it appeared as though everyone lived in peace with each other.

But once I arrived in Myitkyina, I hit barriers. Note that travelers must register with Immigration at the train station or airport; otherwise, you travel at the risk of being detained.

The Myitkyina railroad station was the site of a decisive battle in World War II. Winning Myitkyina with its airstrip and rail station gave the Allies control of Northern Burma and a chance to reconnect India with China via the Burma Road.

I hoped to travel up the Suprabum Road to the Hukwang Valley but was stopped by Immigration. So I visited the local market instead and tried to regroup where the fruits are unlike anything I’ve seen in the western world.

This vendor felt sorry for me and refused payment for some traditional remedies.

Likewise, there was no western medicine  to rid me of the horrible cold I got on the frigid train ride. They don’t have pharmacies in Myitkyina but a wide assortment of natural remedies are sold at the market.

to rid me of the horrible cold I got on the frigid train ride. They don’t have pharmacies in Myitkyina but a wide assortment of natural remedies are sold at the market.

While shopping, I was struck by the presence of so many Chinese in the area. Later I would find out why.

Since I couldn’t go to the Hukwang Valley, I paid for a driver and motorbike to take me to the Mogaung Valley. I had a map from the Immigration office in Myitkyina showing me where I was allowed to travel.

The road to Mogaung, or where the Chindits defeated the Japanese in World War II to secure the Allies’ position in Myitkyina, was dull… at first. Later I was interrogated by gun-toting Immigration guards on my return to town. The poor boy driving the motorbike practically peed in his pants, understandably so, when many are being killed in the battle between the government and the tribes over land rights.

On the way to Mogaung, we were subjected to delays on the road the Chinese were building. Note the meager layers of bedding, gravel, and asphalt slurry. This road will last only a couple of years.

Chinese and the locals worked side by side, carrying buckets of boiling asphalt – something the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) in the US would faint at.

Men, women, and children worked to build the road into the untamed wilderness. Why? To harvest gold, jade, and teak. The workers spent months away from their families, so it was easy to entice them to use their earnings on opium to forget their loneliness.

Ko Zaw Pharkant, a photographer who lives in Myitkyina, took these photos of the mines.

It’s easy to scorn the devastation of land from mining.

But how many of us wear gold or jade jewelry?

It’s not that there is mining in Myanmar that concerned me. They should use the country’s natural wealth to improve the standard of living.

Yet the mining in Myanmar was excessive and the wealth was not going to the people of Myanmar but to their trusted neighbor-the Chinese.

The Chinese are not only building roads to harvest Myanmar’s wealth but there is an agreement between the two countries to build dams on the Chindwin and Irrawaddy Rivers, that would change life for those downstream, forever.

The Chinese are also expanding Myitkyina’s airport. Note the woman on the right in the above photo is carrying a pan of scalding asphalt to cover the thin layer of gravel on the airport runway. Unfortunately for the people of Myanmar, these improvements will last only a few years. Who will stop the Chinese?

Myitkyina WWII airfield in the background. Site of Merrill’s Marauders historic battle.

On November 8, 2015, Aung San Suu Kyi’s party gained control of parliament (Hluttaw) which put them in a position to elect the next president of Myanmar. Before elections, Suu Kyi proactively reached out to the over 135 tribes and 55 parties in Myanmar, including those in the Kachin and Shan states, where the civil war continues.

But Suu Kyi cannot become president because Burmese law states anyone with “legitimate children” who owe an allegiance to foreign powers is ineligible. She has two sons with British passports. It is thought she will rule as a puppet president from a parliament seat.

Will Suu Kyi and her National League of Democracy (NLD) be the harbinger of change that will lead Myanmar out of religious conflict (Buddhist against Muslim), find an economic solution (sign a truce with all tribes), and protect the natural resources of Myanmar from exploitation by their world neighbors?

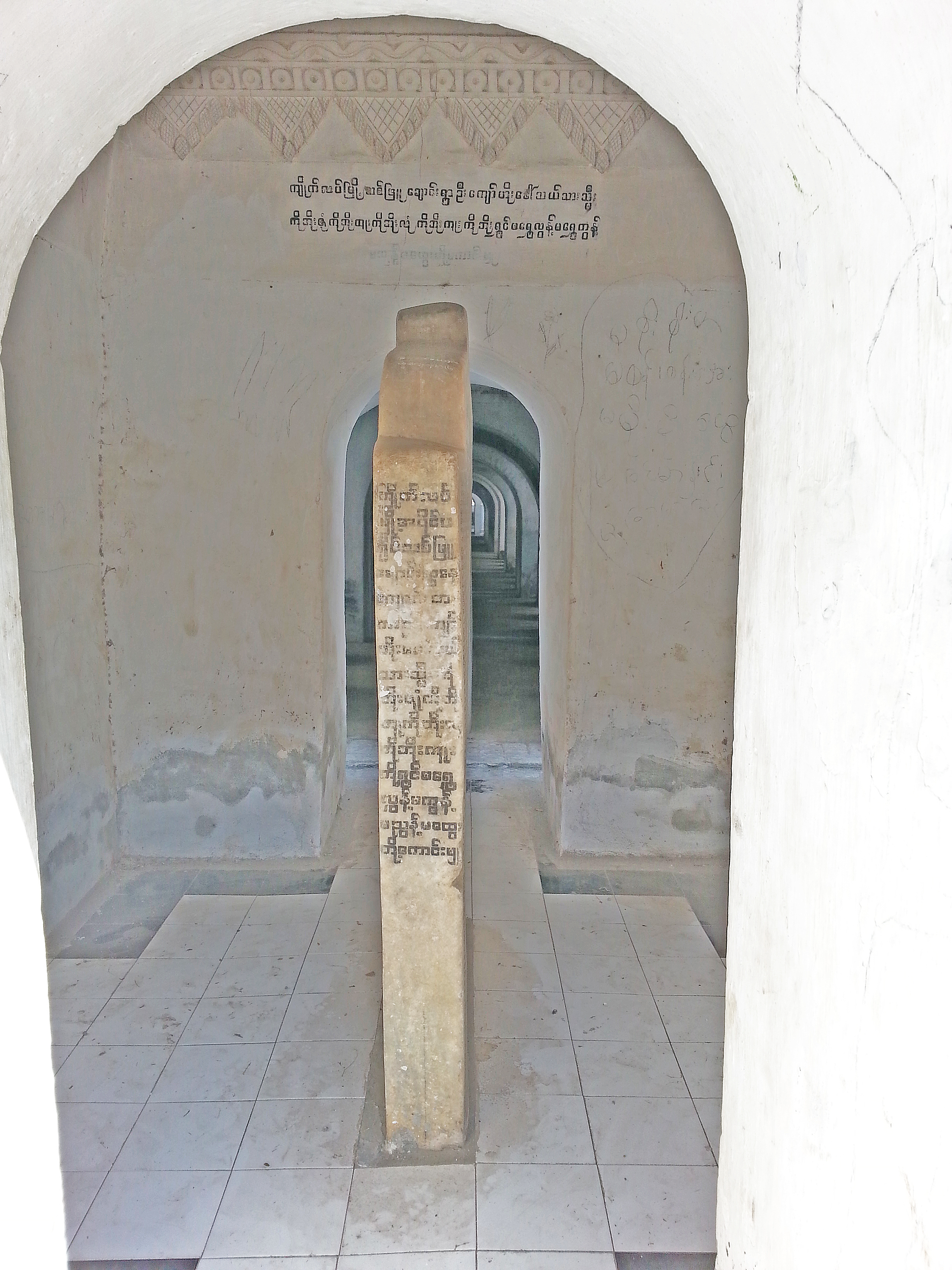

The Kuthudaw Pagoda in Mandalay is surrounded by 729 Stupas

Within each stupa, marble slabs hold inscriptions that make up the world’s largest book.

Other than the monks that tend the site, the pagoda is an amazingly quiet site with very few tourists.

Even with all its tradition, Mandalay is a city of change, with lotteries juxtaposed next to temples and a large gold market attracting tourists on the lookout for inexpensive jewelry. But those who plan to buy gold in Mandalay should ask whether the gem inset is real. Many times the gold is real but the gem is not and likewise, real gems are often set in cheap gilded metal. So ask the vendor what’s real.

There are plans to construct a dam upriver from Homalin to serve the Chinese. It will impact life for those living along the Chindwin and change the entire region in the future.

Some houses on the river are made of teak. But many homes or bashas are made of bamboo. As in India, bamboo is used for everything, from paper to particle board to knit-hats.

The teak is exported abroad. But many old practices are in existence until modern equipment can be transported to the logging sites.

Growing teak trees takes skill. The seeds must be placed in a fire, then soaked in water. Then it takes 45 days for the seeds to germinate.

Previously, Myanmar had implemented British Forestry practices with a 60-year rotation. But given the demand for teak, the regeneration time has been reduced and the quantity of the wood is not as good.

Logs are milled within the country rather than exported abroad to foreign mills, where the finished product fetches a higher price.

Due to a lack of roads in this region, most of the logs are tied together as a raft to be transported to the mill. While watching the log rafts move down river, the novel Sometimes a Great Notion by Ken Kesey came to my mind.

The teak industry is labor intensive. It requires a mobile infrastructure that moves from one log camp to the next after a site has been harvested. Barrels of oil are shipped to the roving logging camps to power portable generators.

Wayward teak rafts are known to disappear, stolen by pirates before they reach their final mill destination.

Men are needed to cut, load, grade, and track the trees. Accounting records held by the government official in the above photo showed 100 logs ranging in size from 12ft diameter x 25ft long to smaller 7ft diameter x 22ft long logs weighing 287,000 tonnes, all contained within one logging raft. Logs that size are most likely from virgin forests, soon to be extinct. So what are the country’s revenue alternatives when teak production disappears? Gold, jade, and opium.

Gold and jade mines provide get-rich-quick job opportunities, but since this work is far from home, the men become bored. Enterprising dealers find ways to help them spend their free time and money on other forms of entertainment, such as opium. It’s not unusual for workers to get lured by the good money then trapped by drugs.

I really appreciate your visit to my web page. It means a lot to me. In the comments box, I’d like to hear what you think about my posts – tell similar stories – share other blog forums.

Error: Contact form not found.

In January 2014, the Chindwin River was not a popular destination for foreigners. I saw no other Caucasian on the voyage traveling upriver between Monywa and Homalin. I was asked several times if I was a missionary (what did that mean?)

The blog below is for those considering a similar trip. Without my guide, Mr. Saw, I would not have been able to purchase boat tickets and find the guest houses at each stop in the time I had to travel. Unfortunately, my time was limited. But I suggest others allow leisurely time in each village and schedule buffer time for the inevitable delays. Costs below are listed in Kyats, which at the time of my trip had a conversion ratio of 1000 Kyats (pronounced chats) to $1 USD. Don’t expect to find banks or atms. Carry both small denominations of Kyats for river travel and USD for places where they won’t take Kyats from foreigners.

Leave Monywa by boat at 3 a.m. Arrive in Kalewa at 5:30 p.m. The trip along the parallel road takes 10 hours.

First-class entertainment was a TV at the front of the boat. High pitch Burmese songs blared non-stop from 3 a.m. until 3 p.m. I was thankful for the cushioned seat rather than a hard bench seat for 14 hours.

Boat Cost for 1st class was: 33,000 Kyats for foreigners and 17,000 Kyats for local residents. You must pay for your guide.

Porters charged 500 kyats to carry my 50-pound bag up the hill.

Many foreigners traveling down the river from Homalin stop at Kalewa and then fly out of Kalaymo, which is inland, rather than continue on the Chindwin to Monywa. The distance from Kalewa to Kalaymo is 20 km or a 2 hr truck ride. If you want to go further to Kennedy Peak, the route the 1942 Ragoon residents took to evade the Japanese, the distance s 70 km (or an additional 50 km west): a 4 hr truck ride.

Leave Kalewa by boat at 11 a.m. Arrive in Mawlaik at 5:00 p.m. Travel from Kalewa to Mawlaik by road is not possible.

At least one bridge was down. If the bridge was serviceable, the road between Kalewa and Mawlaik is 36 km or a 3-hour drive. Without a road, residents have to take the boat and board midstream when the river is too shallow for the boat to go to shore.

After Kalewa, first-class travel changed from cushioned seats to shared metal boxes. A log grader and government lumber inspector shared the first class box with me and my guide. They said it fit six people, but I say it fit four, uncomfortably. Our first-class lodging was 4 feet high by 10 feet wide by 8 feet long with a cotton cloth covering a metal floor.

The cost of a 1st class box between Kalewa and Mawlaik was 20,000 Kyats.

Dinner and breakfast in Mawlaik cost 6000 Kyats, The guest house cost 10,000 Kyats but that was because I stayed longer than 24 hours or beyond the 2 p.m. cut-off time. The Guesthouse, which was located across the street from the police station, let me use their bicycle for free to tour the village. All guest houses have TVs. It was a good opportunity to sit with the locals and catch the news.

I met many geologists during my trip on the river. They were on the river conducting investigations for coal and natural gas. Another natural resource they had no interest in was sand, which was excavated and exported for construction purposes. Unfortunately, the sand excavation resulted in undermining the banks of the river.

To see villages, stupas, and trade along the river was worth the inconvenience. This stretch of the river includes jade and surface gold mines and, like the rest of the river, a lot of teak logging. Early the next morning, in the dense fog, the vendor boats arrived to sell “fast food.”

The cost of a 1st class box between Mawlaik and Homalin was 30,000 Kyats for foreigners. Food on the boat was 5000 Kyats. Once I arrived in Homalin, dinner in town was 2250 Kyats. There are more guest houses in Homalin than in the other villages along the river, but most were full when we arrived at 2:30 p.m. So I ended up at one of the simple places for 10,000 Kyats per room. They kindly provided a pail of heated water for a bucket shower.

Due to the delay on the river, we arrived at the Myanma Airlines office in Homalin at 2:30 p.m. We had to wait around until 5:30 p.m. before the airline office, a nondescript wooden building, opened because they were at the airport acting as ticket takers. There are only two airlines that fly into Homalin, so departure from Homalin is limited to three times per week. If I didn’t get a seat on a plane the next day, I would have been in Homalin for another four days. That would have meant missing other sites I wanted to see in Myanmar.

The plane left in the morning around 8 a.m. The same people who sold the tickets in town, processed tickets at the airport, checked baggage and served as security before boarding. This meant if you were in town and had questions while they were at the airport, you had to wait until the plane departed. There was a separate inspection of my purse, which was conducted in a dark closet by a female employee. I don’t think she could see anything. It’s just that way along the Chindwin, expect the unexpected.

I really appreciate you visiting my web page. It means a lot to me. In the comments box, I’d like to hear what you think about my posts – tell similar stories – share other blog forums.

Error: Contact form not found.

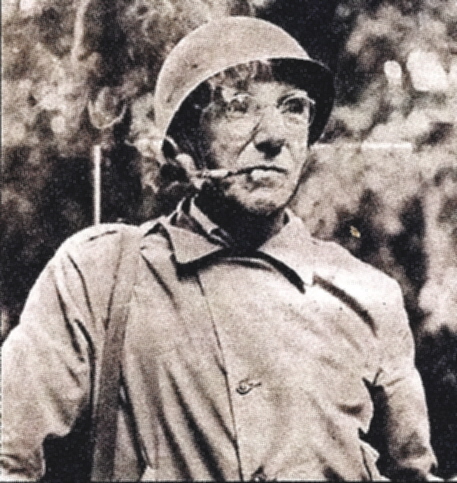

On May 12, 1942, General Joseph Stilwell led 114 Americans, British, Chinese, and Burmese into Homalin. The next day they crossed the Chindwin River. They started in Maymyo on May 1 and arrived in Imphal, India, on May 20. Stilwell knew the Japanese were on their heels so he set a tough pace: fourteen miles per day at 105 steps per minute. Fifty minutes of marching per hour with a ten-minute break. The Japanese arrived in Homalin only a day after Stilwell’s group crossed the Chindwin. In those three weeks, they marched through jungles and up mountains, losing an average of 25 lbs per person.

Later, on May 24, 1942, Stilwell gave an interview to a New Delhi reporter, “I claim we got a hell of a beating. We got run out of Burma and it is humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back and retake it.”

We always hear about the Allies’ journeys through exotic lands. But who did they pass along the way? Below is a day-by-day summary of Stilwell’s retreat and the problems they encountered with photos from Homalin of the type of people they may have seen on their journey.

April 27, 1942, Heard an ugly rumor from a Limie: the Chinese are leaving Lashio (about 100 miles east). Chiang Kai-shek (CKS) said to stay in Burma. But sixty boats have already been sunk by the Japanese on the Irrawaddy River. So we flew all the British women out of and most of the Head Quarters crowd.

April 29, 1942, Swebo was hit by 27 Japanese bombers.

April 30, 1942, Officers are beginning to lose their grip, squabbling over rice and trucks. Lashio was taken. Ava Bridge over the Irrawaddy was blown up by the Chinese to stop the Japanese. There’s imminent danger of disintegration and collapse.

May 1, 1942, The Japanese are on Maymyo Road. We started evacuation from Maymyo at 6 am. Arrived in Zigon at 10 pm. The car stalled. We had a three-hour delay.

May 2, 1942, We left Zigon at 6 am and arrived in Pintha at 11 PM. Battled ruts along the oxen trails. Dr. Seagrave got some medical equipment off a bull cart. Had a bath using a farm well.

May 3, 1942, Left Pintha at 6:30 am and arrived in Wuntho at 9:30 pm. CKS says to go to Myitkyina. Tomorrow we’ll head towards Mogaung. Need to decide whether to wait three days for elephants to carry food or forage later. The bridges needed repair before the trucks could cross. Sent mules ahead to cross Chindwin at Kalewa to see if we could then travel through Kalemyo to Tedim.

May 5, 1942, Myitkyina’s out. We had to make a decision whether to take the route to Tamu, due west of Mawlaik on Chindwin, or head towards Kawlum and cross the Chindwin from Homalin. Chose Homalin. Heard elephants trumpeting in the woods. Broken gas line in the car. Another car got stuck in the sand. A Limie’s truck blocked the ford in the river: he didn’t want to get his feet wet. Then we had to abandon all vehicles and find another crossing. Serious fords to cross with the monsoon. Saw the head man of the village. Told us all coolies went south. Now it will take 10 days to get rafts or go to next village, which has 60 porters and mules. Good eggs (people) here.

May 6, 1942, Late start at 3:30 am. Last radio message – then we destroyed the radio

May 7, 1942, Arrived in Magyigan. Hard going across the river. Some carried mattresses and bedding. Stripped everyone down to only 10 lbs per person. Of the 12 officers, 4 are seriously ill. Merrill fell face first. Christ, but we are a poor lot. Marched down the middle of Chaungyyi River rather than fight the vegetation along the shore.

May 8, 1942, Arrived in Saingkyu. Chattering monkeys in the jungle. Japanese bombers were overhead. We’re not out yet. Had tea and a good sleep.

May 9, 1942, Arrived in Maingkaing – Charged by a rogue elephant. Began traveling on a flatbed raft with bamboo hand poles on the Uyu River.

May 10, 1942, Put Seagraves Burmese nurses on the roof of rafts. Nice ride but too damn slow. Took a break at 22:00, then poled all night on the river.

May 11, 1942, Rain. That’s ominous. Had a hell of a time getting everyone going. Big chicken dinner. Off again at 22:00. Many snags and rafts breaking up. Rumor preparations were made for us in Homalin.

May 12, 1942, Arrived in Homalin. It’s Mother’s Day. No one’s here. Commissioner up river. Camped in a temple.

May 13, 1942, Left at 6 am and traveled 3 miles north of Homalin to cross Chindwin by dugouts. After we crossed, one of the guerilla leaders took his horse through the chowline. “What will I do with him?” Thunderstorm ahead.

May 14, 1942, Passed by a bright green snake. Sissy Brig complaining. Climbed in heavy rains to Kawlum. Met British relief expedition with ponies, medical supplies, and food.

May 15, 1942, Time change. Beautiful view of Mainpur Hills.

May 16, 1942, Met Tangkhul bearers. Fine people. Haircut like Iroquois. Men wore g-string sashes. Arrived in Chamu – beautiful view. Thatched covered bridge. Coolies built me a house in an hour.

May 17. 1942, Seventeen miles to Pushing. Naga came out with rice wine to welcome the “great man.” Pushing like Alaska with totem pole boards. I Saw Tangkhul with safety pin earrings.

May 18, 1942, Six miles to Ukhrul. A noisy night with bugs. Tangkhuls wear a ring on their dink while working in the fields with the women. Women strip down to nothing with the heat. Imphal bombed again.

May 19, 1942, Rained. Passed through Limpo. Made 21 miles. Got cigarettes and chocolate.

May 20, 1942, Rained all night. Cordial reception by Limies. The PA, an old fart, didn’t know I wanted him to forward the radio message from May 6. Colossal Jackass.

I really appreciate you visiting my web page. It means a lot to me. In the comments box, I’d like to hear what you think about my posts – tell similar stories – share other blog forums.

Error: Contact form not found.

January 5, 2014

I borrowed a bicycle and joined U Thant Zin for a tour of the abandoned British village within Mawlaik.

Let me take you back to 1916.

To support the teak trade along the Chindwin, the British imported their way of life from back home. So Mawlaik has a golf course, although the grass is not always cut these days.

The clubhouse appears to have been the center of social gatherings during the Victorian era. I suggest you read Burmese Days by George Orwell to get an understanding of how important the clubhouse was to those wanting to keep a link to the motherland, which was at least a month-long journey back home.

The teak trade must have been brisk to have built such a large government complex in a remote area like Mawlaik.

Another by-gone British building is the Christian church.

It even has a bell tower, shy a bell. Imagine being a Buddhist and hearing the bell every Sunday and maybe for weddings, too. Caucasian women from Britain were enticed to visit Burma for just such ceremonies.

The Myanmar government is funding the restoration of several old British buildings in Mawlaik. But it’s not easy to get there. So why the investment? Maybe the backdrop for a BBC production?